Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

Welcome to the final part in our series about social change strategy.

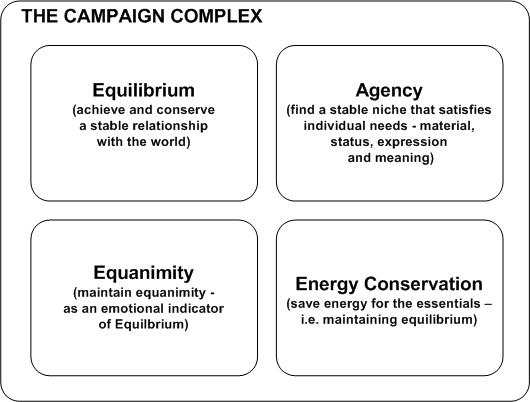

In part 1, we proposed a “Campaign Complex” comprised of four “biological” Principles – Equilibrium, Agency, Equanimity and Energy Conservation – which might account for some common challenges experienced by change agents. We outlined some strategies for successful campaigning suggested by these Principles.

In part 2, we proposed and discussed a “missing” fifth “Community Principle” implied by the other four, and suggested that some technologies – particularly transport and communications – may have facilitated its disintegration, by enabling “Agency” to bypass the constraints of geographical community.

In part 3, we discussed the benefits and costs associated with freedom from the “Community Principle”. We postulated that, ultimately, cultural and personal costs outweigh the benefits, and that resulting vicious circles may underpin and reinforce common campaigning bugbears.

In this final part, we will outline a Case Study which illustrates some of the positive characteristics of the Campaign Complex, particularly the Community Principle. We also propose the control parameters responsible for the re-emergence of the Principle in this context, and the implications it could have for change-oriented organisations.

Reactivating the Community Principle

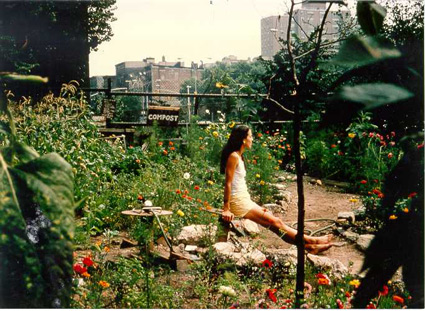

In recent years, communities around the world have begun to exhibit a profound collective response to environmental crisis and encroachment by harmful industrial development.

This has frequently been sparked by onshore unconventional gas development (“fracking”, coalbed methane or coal seam gas, and underground coal gasification). Notable exemplars include the Community Bill of Rights Movement in the USA, and the “Lock the Gate” Alliance in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales, Australia.

One such case, of which Arkadian has first hand experience, is the Falkirk Against Unconventional Gas campaign. This began in September 2012, when residents of a Scottish community received notification of a proposal by Dart Energy to extract coal bed methane near their homes – the UK’s first application to commercialise the Dash-for-Gas.

Fragmented information-sharing initiatives by community councils and local residents soon coalesced into a series of general public meetings. Here, individual concerns about impacts on health and property values evolved into a general concerns about a common threat to community Equilibrium and Equanimity.

Meetings were supported by structured group decision-making and independent third-party facilitation. These processes complemented the Agency Principle by enabling a diverse group of residents to pool individual expertise and share equal ownership of outcomes.

The collective response emerged in the form of two groundbreaking documents.

The first was a pro-forma objection letter – the Community Mandate – which began with the community’s visions of 20yrs in the future – one born from local council policy and residents’ aspirations, and the second, what the area might look like if the industry rolled out. It also set out residents’ evidence for suspected risk and their own minimum requirements for its assessment and regulation.

3 months later, over 2500 had been signed and submitted, including representation by over 80% of some affected villages.

A group of residents, each with modest door-knocking goals (satisfying the Energy Conservation Principle) in a short time achieved the biggest response to a planning application in the history of the local authority.

The second document – the UK’s first Community Charter – wholly redefined the narrative from “fighting against” to “fighting for”. Drawing from the Mandate’s positive vision, the Charter set out those shared assets, values and aspirations – termed “Cultural Heritage” – which were agreed by consensus to be fundamental to local health and well-being.

Assets, agreed unanimously, included the goal of a clean and safe environment, the healthy development of children, the sanctuary of the home, the diversity and stability of the local ecosystem, the resilience and continuity of the community. and trust in elected representatives.

The Charter also set out the community’s basic right and responsibility to safeguard and improve their “Cultural Heritage”, in order that they could pass it onto future generations in a better state than they inherited it.

This provided a remarkably detailed and concrete definition of that notoriously slippery term: “sustainable development”. It also illustrates that it’s only really meaningful if delineated and maintained by general consent at a local level.

This broadening of “Cultural Heritage” to encompass the fabric of interrelationships that creates community, including both tangible and intangible assets, also finds support in the Council of Europe Framework Convention.

The Charter has since been adopted by 3 local Community Councils, half of all Local Authority Councilors and an ever-growing number of local farmers and residents. It was also recognised by Scottish Government as requiring a special session in the recent public inquiry to decide the application, the UK’s first in relation to the Dash-for-Gas. Here, and in later Hearing sessions (see below), local residents, farmers and councilors gave evidences about the impact of the development on their aspirations and experience.

Regardless of the outcomes of this public inquiry, nothing seems more likely to succeed, ultimately, than a community thinking and acting together to protect the shared fundaments of its Equilibrium and Equanimity.

And the Control Parameters?

1) A COMMON THREAT (AND PURPOSE) PERCEIVED;

2) A vision of what true Equilibrium and Equanimity look like (set out in the Community Mandate and Charter);

3) A few souls brave enough to cold-call an unknown neighbour;

4) Simple processes which supported collective assessment and decision-making (Agency Principle); and

5) Modest collective goals and successes at the outset (Community and Energy Conservation Principles).

That’s all!

It didn’t take much for people to feel re-empowered by the wisdom and the scale of what could be achieved together, and why this was important. Negotiating a diversity of perspectives has involved conflict and compromise (neither much appreciated by “Agency”), but the compensations have been more than worth the pain – collective vision and support, social learning, and novel opportunities for individual expression, powerful friendships, and fun.

Moreover, though Part 2 suggested some technologies facilitated the disintegration of Community, the same technologies here have played an invaluable role in maintaining strategic communications among residents, and with other community groups and experts across the globe. The technology itself is neutral and while it may offer “Agency” easy routes to self-satisfaction, in the service of collective purpose it has been a powerful mechanism to support face-to-face activities.

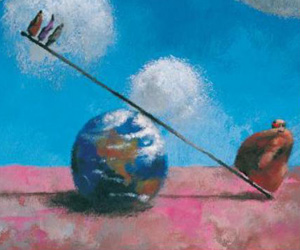

To conclude, in this light perhaps unconventional gas could represent a genuine opportunity for the UK, and not the one espoused by the industry and Government? The Dash-for-Gas represents a clear and immediate threat to thousands of communities. Unquestionably, costs at a local level outweigh the benefits. Two thirds of the UK are earmarked for exploitation.

Thus, key control parameters necessary for re-activating the Community Principle seem present and on an extensive scale. If the response by Falkirk, Canonbie, Balcombe, Fenhurst, Barton Moss, and many many others communities across the UK and the world, are harbingers of what’s to come, then we should be reassured and, indeed, get stuck in.

In the absence of a viable alternative to our current system, the power for transition lies not with the UN, or the EU or National Government, or in a strong brand or campaign, but emergent right on our doorstep. There is no political will without public will, and the Campaign Complex suggests the latter hinges on our participation in, and ownership of, the what, how and why of change.

Arkadian is coming to the view that such processes can only really be concrete, practical and meaningful in a local context, that they require people to get together in the same room, and that due to cultural and technological factors they’re unlikely to happen without certain control parameters in place, most notably a perceived common threat or purpose.

Nevertheless, there’s also no question that acting effectively, in concert, is a biological capacity conferred by evolution, and lies latent just below the surface despite Agency’s best efforts to deny and suppress it. Indeed, the balance conferred by the Community Principle may be the only thing now that can prevent Agency chasing money off the cliff with all in tow. The rewards of reactivation, on the other hand, seem manifold.

Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

This is a 4-part series which proposes a framework – the Campaign Complex – which may explain some common campaigning barriers and successes, and could inform practical strategy for community groups, campaigners and NGOs.

In Part 1, we outline the framework and its 4 component Principles, each of which may have a general adaptive purpose for all animals.

The idea of the Campaign Complex emerged from the analysis of a focus group of seasoned change agents, the loose aim of which was to explore how organisations with similar values, but different foci, might work in a more mutually-supportive way.

The discussion circle was structured around personal responses to the following three questions (written on post-its and stuck on the wall for reference during the conversation):

- 1) What motivates a change agent?

- 2) What are the barriers to a successful campaign?

- 3) What has worked at overcoming these barriers?

Despite the wide diversity of campaigning knowledge and experience in the mix – political party, banking reform, community gardening, social change, national Climate Change, Occupy, community opposition to unconventional gas – there was a surprisingly strong agreement on what had and hadn’t worked.

However, in the analysis, oft-cited barriers to success – ignorance, gullibility, apathy, carelessness and denial – seemed to offer an incomplete and superficial account of the themes.

The framework that emerged was much influenced by Arkadian’s concurrent involvement in local opposition to unconventional gas extraction, which offered first-hand experiences of positive and negative campaign dynamics, and also the author’s PhD Research, which is exploring child development from a biological systems perspective.

There follows an overview of the 4 Principles that make up the Campaign Complex, their proposed evolutionary adaptive purpose, how their effects manifest in our lives and their possible consequences for campaigns.

To close, we shall outline some of the Complex’s strategic implications for positive change.

THE CAMPAIGN COMPLEX

Purpose. The primary purpose of the animal nervous system is to construct and maintain a stable and predictable relationship with the immediate environment.

Purpose. The primary purpose of the animal nervous system is to construct and maintain a stable and predictable relationship with the immediate environment.

Effects. Once we’ve established a workable pattern of interrelationship with our everyday world – routines / capacities / opinions / property / social relations etc. – we will tend towards experiences which build on it, and avoid those which might threaten its integrity or interrupt its flow.

Consequences. Even when we intellectually or morally appreciate the goals of a campaign, meaningful engagement may be challenging if it entails any implication of change to our ways of life and thinking, or any risk of losing face, identity, property or employment. A perceived, possibly unconscious, threat to stability could be why change agents frequently encounter dismissive, disapproving or defensive responses from their immediate and wider society.

2) The Agency Principle:

Purpose. An individual animal’s primary directive is to negotiate and maintain the resources, territory and freedom necessary for successful survival, reproduction and self-fulfillment.

Purpose. An individual animal’s primary directive is to negotiate and maintain the resources, territory and freedom necessary for successful survival, reproduction and self-fulfillment.

Effects. We tend towards experiences which confer control over decisions important to our sense of material and social stability, which provide support and appreciation for our individual needs and expression, and avoid those where such agency is absent or at risk.

Consequences. We’re unlikely to commit to a campaign if we’ve no involvement in determining goals and activities, are insecure about the knowledge and skills it may require, or believe our contribution is insignificant or unappreciated. If we do, we may unconsciously undermine leadership and approaches, or overplay our role. On the other hand, when we lead, criticism of our good intentions may leave us feeling frustrated, confused and isolated.

3) The Equanimity Principle:

Purpose. Stress is the animal response to a threat to equilibrium or agency. It motivates flight or fight action with the goal of achieving the equanimity indicative of a stable experience of world and self.

Purpose. Stress is the animal response to a threat to equilibrium or agency. It motivates flight or fight action with the goal of achieving the equanimity indicative of a stable experience of world and self.

Effects. We will tend to avoid stressful information and experiences, unless they relate to an immediate and unavoidable danger, and seek those which confer individual reassurance and pleasure.

Consequences. By evading distressing truths, we often grow ignorant of the need for change the emotion is supposed to motivate. Without our sponsorship, vital sources of information and action fade or are curbed. By comfort-seeking, we often fuel toxic cycles of consumption – the c21st’s default route to well-being.

4) The Energy Conservation Principle:

Purpose. Animal behaviour largely presumes an erratic energy supply. Available resources are usually stockpiled and used frugally and efficiently to pursue equilibrium, agency and equanimity.

Purpose. Animal behaviour largely presumes an erratic energy supply. Available resources are usually stockpiled and used frugally and efficiently to pursue equilibrium, agency and equanimity.

Effects. We tend to avoid non-essential goals and tasks that entail, or might entail, unnecessary cognitive or physical energy or which someone else will tackle if we don’t, and favour those yielding maximum immediate reward for minimum effort.

Consequences. We are unlikely to engage with a campaign which implies long-term commitment, doubtful victory, a taxing work / info load, or which appears to be ticking along fine without us. On any given task, we will seek efficiencies and, given a range of ways of participating, we are likely to elect for the easiest.

STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS OF THE CAMPAIGN COMPLEX:

1) EQUILIBRIUM: Campaigns will have greater likelihood of success if they are perceived to be safeguarding what we collectively value and what is integral to the stability of our everyday lives. We are more likely to engage if we think we stand to lose or change more through our inaction, than our action. We are also likely to need significant practical and moral support for activities which are unfamiliar to us, no matter how basic they seem to others.

1) EQUILIBRIUM: Campaigns will have greater likelihood of success if they are perceived to be safeguarding what we collectively value and what is integral to the stability of our everyday lives. We are more likely to engage if we think we stand to lose or change more through our inaction, than our action. We are also likely to need significant practical and moral support for activities which are unfamiliar to us, no matter how basic they seem to others.

2) AGENCY: Campaigns with common purpose, which co-develop goals, roles and actions through facilitated, collective decision-making processes are more likely to work because they give us an opportunity to express agency and feel ownership of outcomes.

2) AGENCY: Campaigns with common purpose, which co-develop goals, roles and actions through facilitated, collective decision-making processes are more likely to work because they give us an opportunity to express agency and feel ownership of outcomes.

3) EQUANIMITY: Campaigns are most likely to motivate us if they address an immediate, common threat to equilibrium or agency, thus provoking a “fight” response. Moreover, visible evidence of support is, in turn, more likely to inspire action because “fighting” together is more likely to succeed (though it can also offer us a cover for inaction – see below).

3) EQUANIMITY: Campaigns are most likely to motivate us if they address an immediate, common threat to equilibrium or agency, thus provoking a “fight” response. Moreover, visible evidence of support is, in turn, more likely to inspire action because “fighting” together is more likely to succeed (though it can also offer us a cover for inaction – see below).

Collective action will provide further reinforcement if it also offers us opportunities for fun, enjoyment and socializing. Such activities could also mitigate the risk of campaign disintegration as the result of stress causing us to become preoccupied with our own self-preservation, and lose sight of the needs and goals of the group (the dynamics of which will be explored in Pt 2).

4) ENERGY CONSERVATION. Simple first-step experiences, which imply no commitment but deliver rewards that resonate strongly with the other principles, are most likely to facilitate our deepening involvement. Regular “heartbeat” meetings and events can promote habits which override our excuses and inertia.

4) ENERGY CONSERVATION. Simple first-step experiences, which imply no commitment but deliver rewards that resonate strongly with the other principles, are most likely to facilitate our deepening involvement. Regular “heartbeat” meetings and events can promote habits which override our excuses and inertia.

Lastly, if our engagement tails off, we need carefully-worded unemotional feedback about the potential consequences of our inaction. If we don’t know our non-participation threatens what we value, then this principle predicts we’re unlikely to do anything about it.

So there’s the Campaign Complex in a nutshell. We hope you’ll join us next Friday for Part 2, when we shall be proposing a vital “Missing Principle” inferred from the dynamics and implications discussed here.

Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 2: The Principal Themes (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

This is the second installment of a 4 part series about a soft systems workshop Arkadian ran with 20 PhD candidates at the Future Connections Conference 2012 in St Andrews, all of whom were conducting PhD Research on the theme of Sustainable Development.

Previously, we outlined the workshop structure, and described the session’s major outcome: an Action Plan for seeding a nationwide Viable Alternative to the current economic system. In the last two installments, Arkadian will be venturing some personal thoughts relating to the session outcomes that emerged during the analysis.

This week, however, we will be exploring four Themes that pervaded the discussion about a Prototype Community that might seed a Viable Alternative. As mentioned previously, some ideas here (and in Part 3 and 4) will be developed beyond the original session content as a result of their transaction (via Arkadian) with an ongoing experiment in developing an socioeconomic alternative (‘Wisdom Economy’) on the Isle of Bute: An Tearman.

1) Stewardship of the Diversity, Integrity and Beauty of the ‘Community-of-Interdependence’ (Nature first). It was generally agreed that, if the Community was to have a single guiding principle it should be the pursuit of a reverent partnership with Mother Nature. This combines active observation and experimentation, to enrich our objective understanding of Her systemic workings, and activities which promote a deeper experiential connection, and appreciation of Her intrinsic value.

Although we place Nature first, as concerns practicing empathy for other and placing systemic needs above our own, our values are equivalent towards both Her and Our Community. We aim to cultivate individual awareness that the two are not separate but together constitute a single Community-of-Interdependence within which every ‘being’ performs a substantive role.

Although we place Nature first, as concerns practicing empathy for other and placing systemic needs above our own, our values are equivalent towards both Her and Our Community. We aim to cultivate individual awareness that the two are not separate but together constitute a single Community-of-Interdependence within which every ‘being’ performs a substantive role.

The fundamental goal of the Viable Alternative is to establish an equilibrium where we receive our material and non-material needs as a byproduct of enlightened care for the Community-of-Interdependence, with Nature taking priority. In pursuit of this, we complement Her strategies of achieving systemic integrity, productivity and beauty through diversity, reciprocity and work excellence in our approaches to the local ecology and our social milieu.

2) Performative Knowledge and Learning (Community-as-Process). How a rag bag of individuals, and hang-ups, might operate together effectively, ethically and enjoyably was probably the main, if subliminal, preoccupation of the session. Ultimately, this led to the group insight that ‘Community’ is a continuous reinforcing process, and not a ‘place’ or ‘entity’ as the concept is more commonly used.

To think and act as a unit (‘togetherness’, ‘belonging’, ‘sharing’), our individual purpose, needs and experiences need to braid and coalesce with each others’. This couldn’t happen without the Structure, Principles and, particularly, the Time that would enable the Community to successfully plan, work, have fun and be together.

To think and act as a unit (‘togetherness’, ‘belonging’, ‘sharing’), our individual purpose, needs and experiences need to braid and coalesce with each others’. This couldn’t happen without the Structure, Principles and, particularly, the Time that would enable the Community to successfully plan, work, have fun and be together.

Also considered essential to acting as a unit is the ability for all members to have some grasp of the whole ‘blueprint’ of their particular Community project and, thus, an appreciation of the role, value and interdependence of all actors and activities therein. This requirement for inclusive participation in, and understanding of, the whole picture, in turn, implies limitations on the scope, size and organisation of the ‘units’ that comprise the wider Community System.

Moreover, there are no ‘experts’ here. Other, that is, than the Community itself. We consider the only real knowledge and learning is that which arises from, and returns to, our collective performance.

Know-how, erudition, irreverent cross-disciplinary romps, naive childlike experimentation, error and dispassionate collective assessment are all celebrated contributors to our ultimate purpose: a continuous social learning process that calls forth the unknown and unknowable world of the Viable Alternative. In this milieu, articulated knowledge functions as a part of collective activities rather than as an expertise that structures performance from without.

Know-how, erudition, irreverent cross-disciplinary romps, naive childlike experimentation, error and dispassionate collective assessment are all celebrated contributors to our ultimate purpose: a continuous social learning process that calls forth the unknown and unknowable world of the Viable Alternative. In this milieu, articulated knowledge functions as a part of collective activities rather than as an expertise that structures performance from without.

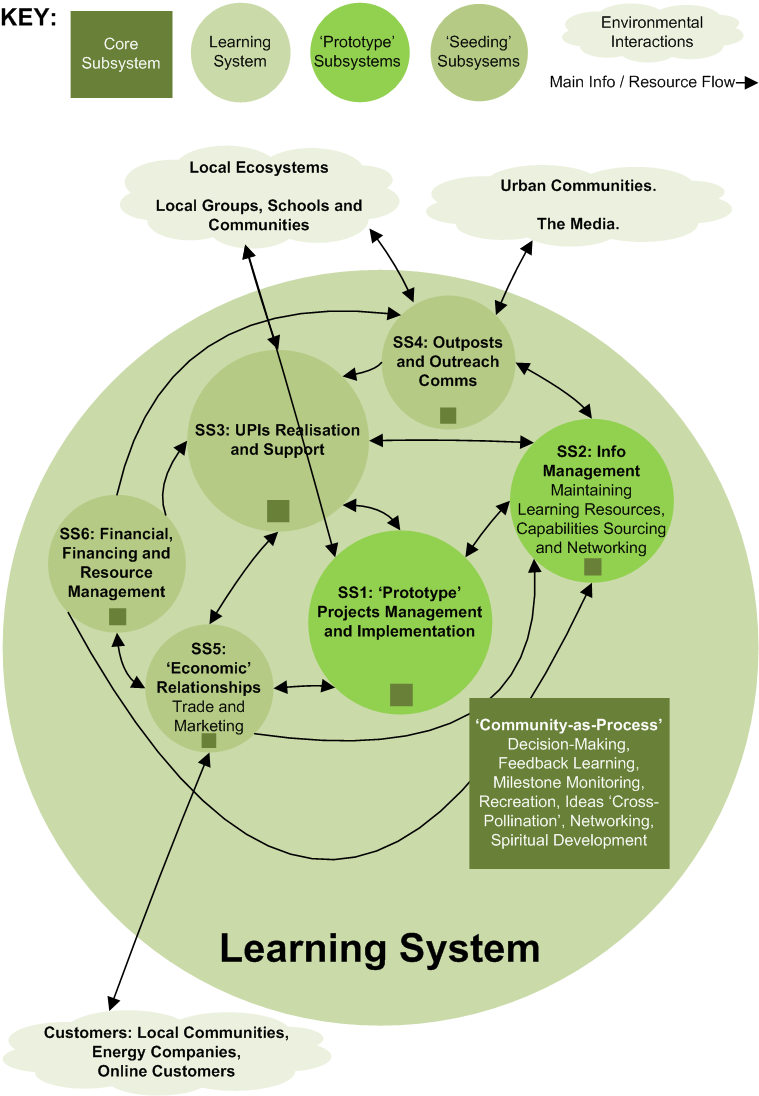

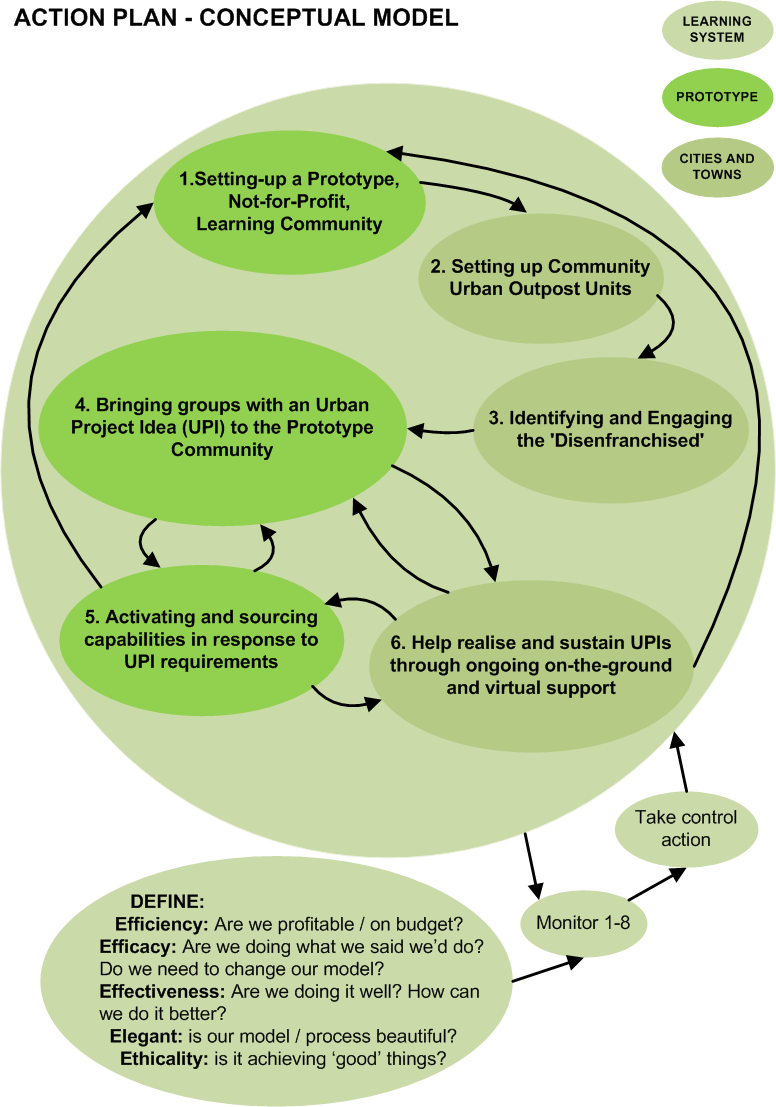

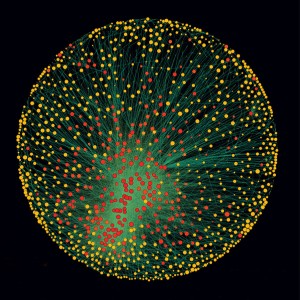

Below is a diagram of a Viable Systems Model (VSM) representing the Community’s organisational structure, which demonstrates the centrality of Community-as-Process’ to its success. A VSM is a systems thinking tool that applies the metaphor of living organism to an organisation, representing its main purposeful transactions with the environment as ‘organs’.

Ordinarily, a VSM presumes an ‘Executive Subsystem’ that monitors and orchestrates the operations of the whole – the equivalent of, say, the ‘The Board’ or the Prefrontal Cortex. However, in the model of the Viable Alternative Learning System, the wisdom of the ‘Director’ has been displaced by that of the ‘Collective’, in the form of the social processes from which our shared self-organising and self-regulating vision emerges.

3) Respect and Empathy for The Experiences of Other. Key to the healthy functioning of ‘Community-as-Process’ is respect for the predispositions and experiential histories of our fellows, even when they give rise to motivations, perspectives and worldviews very different from our own. Necessarily, this also entails developing our aptitude for dispassionate self-examination, so that we may each reflect critically on the roots of our own models, assumptions and prejudices.

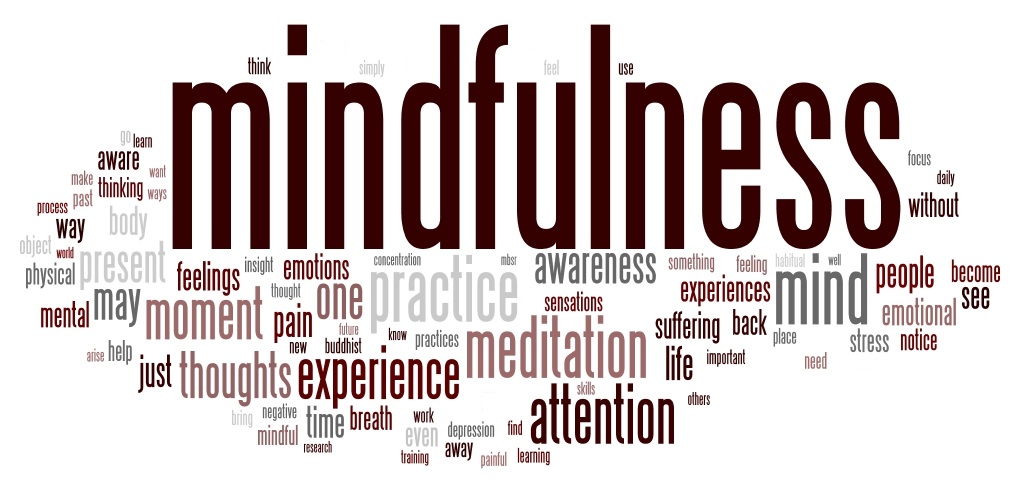

To address these inner challenges, our aim is that everyone become adept in the pragmatic application of ‘tools’ that promote mindfulness of self and other – meditation, yoga, mediation, facilitation, discussion circles, non-violent communication, nature connection and systems methodologies such as Rich-Picturing, SODA and SSM.

The practical objective of all this is, to the extent possible, decouple personal experience from its deep cultural (and possibly, natural) entanglements with status, identity and ego, so that it’s performative potential may blossom. Deconstructing our ivory towers to build bridges of consensus. Transforming Knowledge and Experience as immutable personal possessions, into Knowledge and Experience as a dynamic shared property that informs and feeds back from impersonal activities-in-the-moment.

All very well, I hear you say, but what about me? Where do my individual needs fit in and what happens when they diverge from those of the collective? After all, even big happy families stifle personal growth at times, don’t they?

Making space for purely personal development, unsurprisingly, was another central theme of the discussion. As mentioned in the previous installment, a core design objective of the Prototype is to free a third of each week for each of us to pursue our own ‘becoming’ according to our own inclination. Our only constraint is that in exercising this right, we don’t impact negatively on the diversity, integrity and beauty of the Community-of-Interdependence.

Making space for purely personal development, unsurprisingly, was another central theme of the discussion. As mentioned in the previous installment, a core design objective of the Prototype is to free a third of each week for each of us to pursue our own ‘becoming’ according to our own inclination. Our only constraint is that in exercising this right, we don’t impact negatively on the diversity, integrity and beauty of the Community-of-Interdependence.

The Community may also allocate some of its own ‘activity and decision-making’ time to develop opportunities and environment in response to individuals’ identified or declared needs. This is deemed valuable work because it promotes diversity and redundancy, the magical underpinnings of productivity and stability for both Nature and Community.

In summary, we take the view that a social system where individual variety, creativity and knowledge of the local natural environment flourishes according to its own will, where each node maintains positive interconnections to all others and contains the seed of the self-sufficient whole, and which can decide and mobilise effectively as a single organism, is one of optimal adaptability and resilience, and thus best equipped to face the environmental challenges of the future.

In summary, we take the view that a social system where individual variety, creativity and knowledge of the local natural environment flourishes according to its own will, where each node maintains positive interconnections to all others and contains the seed of the self-sufficient whole, and which can decide and mobilise effectively as a single organism, is one of optimal adaptability and resilience, and thus best equipped to face the environmental challenges of the future.

4) The Sanctity of Time for Community and The Individual had, by the end of the session, become a central mantra of the Learning System. Time is not perceived here as an abstraction, or an economic ‘obligation’, but as a resource of inestimable importance: the root source of those experiences most responsible for generating meaning, community and well being.

Thus, the need for the Viable Alternative to produce sufficient Time to satisfy our non-material requirements was a thread that pervaded the discussion. An indicator, possibly, of how overlooked, undervalued and misunderstood its role has become in the current economic system.

And so concludes our look at the principal 4 Themes underpinning the discussion, and of the outline of the session outcomes. We hope you’ll join in a fortnight for Part 3, where Arkadian will be discussing some personal views that emerged during the analysis.

Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

This article is the first in a 4 part series relating to a soft-systems workshop Arkadian ran at Futures Connections 2012. The first 2 parts deal primarily with the outcomes of the session, whilst in the latter 2, Arkadian will be setting out some personal thoughts resulting from the analysis.

Participants were 20 PhD candidates from universities across Scotland, representing a broad variety of disciplines. All were conducting Research on the theme of Sustainable Development.

Since Futures Connections, the outcomes of this workshop have informed the decision-making of another project in which Arkadian is involved: An Tearman, on the Isle of Bute. An Tearman is an experiment in enacting a new socioeconomic model (‘Wisdom Economy’) involving a broad range of stakeholders. A prototype ‘blueprint’ heavily influenced by Permaculture principles is slowly emerging.

Since Futures Connections, the outcomes of this workshop have informed the decision-making of another project in which Arkadian is involved: An Tearman, on the Isle of Bute. An Tearman is an experiment in enacting a new socioeconomic model (‘Wisdom Economy’) involving a broad range of stakeholders. A prototype ‘blueprint’ heavily influenced by Permaculture principles is slowly emerging.

As the ideas generated by the workshop have contributed to the An Tearman project, so too have Arkadian’s learnings fed back into the current analysis, impacting on interpretations, and resulting in some development of the original workshop material, particularly in Parts 2, 3 and 4.

Next episode, we shall be discussing 4 Themes that pervaded the discussion, and in the last two installments, we’ll explore some ideas pertaining to the session outcomes. However, to begin we will outline the aims and structure of the workshop and describe its main outcome: An Action Plan for seeding a Viable Alternative.

The session’s Overarching Aim was:

WHAT?: To seed nationwide sustainable development.

HOW?: By building a self-sufficient and sustainable Community which demonstrates an inspiring, working model of a viable alternative to the current economic system.

WHY?: Because if we desire a tolerable future, there is an urgent necessity to begin our transition to a sustainable economy.

Participants were asked to consider 3 questions:

WHAT Personal Project would you bring to this Community?

HOW would it contribute to the Overarching Aim?

WHY is it important?

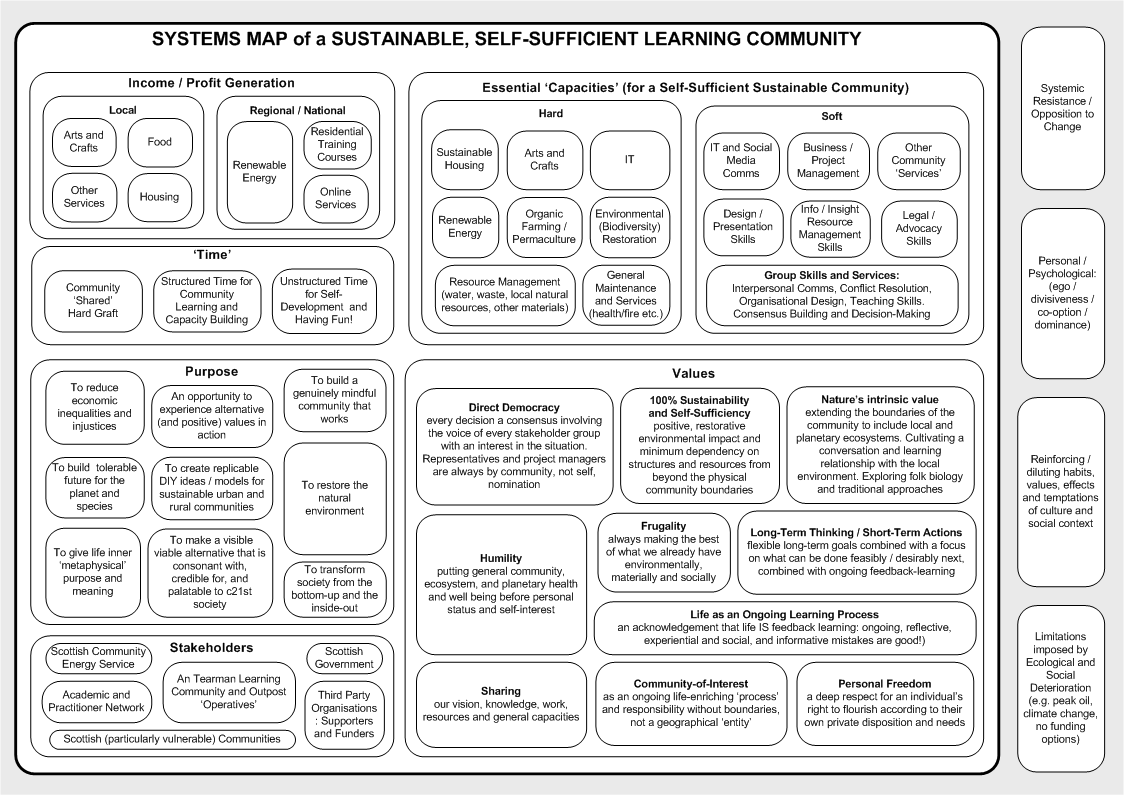

Responses were written on Post-Its in private and stuck randomly on a wall in What? / How? / Why? groups. The result fueled the group discussion. A Systems Map representing rough categories for the Post-Its and main topics of conversation appears below.

The main outcome of the session, unexpectedly, was an Action Plan for seeding nationwide sustainable development. This was as follows:

1. Set-up a Prototype Not-for-Profit Learning Community, which incorporated all the essential capacities of a nationwide sustainable Viable Alternative to the current economic system (see Systems Map: Essential ‘Capacities’). In other words, a ‘whole-system’ Prototype in miniature.

The original Community is envisioned as a cross-pollination of practical experiment and virtual network. At the outset the burning objective of the practical experiment is to generate zero impact revenue streams and become profitable (see Systems Map: Income / Profit Generation).

The virtual network is comprised of experts representing a wide variety of disciplines and experiential backgrounds who, whilst unable to commit substantial time to the practical experiment, are willing to contribute to decision-making whenever situation-specific expertise is required.

Community Time is split equally three ways:

(i) Collaborative physical transaction with the natural environment.

(ii) Structured time for community activities and decision-making. While this also includes the management of social groups and events, the major proportion of this time involves mindful and transparent group reflection upon both the practical experiment and social dynamics. Models, measures-of-success and next step actions are then co-calibrated in response to what has been learned.

Overarching decision-making and consensus-building are all highly-structured processes. They are third-party facilitated and knowledge is externalised using visual tools so as to depersonalise and depolarise opinion. All members are always involved, irrespective of subject, age or expertise. Thus, judgments and learning are informed by the broadest diversity of experience, and the emerging blueprint for the Viable Alternative is shared by all.

(iii) Unstructured time for personal development according to individual inclination. Spiritual, knowledge and skill development, leisure and recreational activities, time for special relationships, FUN? This is ‘You’ time, however you wish to spend it.

One of the central aims of the physical experiment is to generate a minimum of 4 free days every week for (ii) and (iii). Whilst profitability is undeniably important, it plays, and will always play, second fiddle to the meeting of the Community’s deeper non-material needs.

2. Setting up Community Urban Outpost Units. Now that our Prototype is stable, we use some of our assets to fund the despatch of ‘advocates’ to cities and large towns. As urban areas are where the current economic system is most resistant to change and its inequities are suffered most acutely, we believe it is here that successful exemplars of a Viable Alternative will achieve the most resonance.

2. Setting up Community Urban Outpost Units. Now that our Prototype is stable, we use some of our assets to fund the despatch of ‘advocates’ to cities and large towns. As urban areas are where the current economic system is most resistant to change and its inequities are suffered most acutely, we believe it is here that successful exemplars of a Viable Alternative will achieve the most resonance.

3. Engaging the ‘Disenfranchised’. Our advocates seek out and engage those groups that have a vested interest in a Viable Alternative. Perhaps the most obvious are young and disadvantaged peer groups, who have social capital but a bleak, hopeless future under the current system. We share the Prototype ‘blueprint’ with them, and encourage them to think about how they could positively transform their own environment in order to meet local needs.

3. Engaging the ‘Disenfranchised’. Our advocates seek out and engage those groups that have a vested interest in a Viable Alternative. Perhaps the most obvious are young and disadvantaged peer groups, who have social capital but a bleak, hopeless future under the current system. We share the Prototype ‘blueprint’ with them, and encourage them to think about how they could positively transform their own environment in order to meet local needs.

4. Bringing groups with an Urban Project Idea (UPI) to the Prototype. Groups with strong ideas, a willingness to learn, and a commitment to implement their UPI, are invited to the Prototype for experiential immersion in Community work, principles, values and decision-making. Stepping ‘outside’ of their everyday lives enables the groups to reflect upon their UPI with greater clarity and objectivity, and plan free of those shadowy constraints – models, relationships, habits, cues etc. – that hamper decision-making within context.

The group’s transition into participating in our emergent ‘blueprint’ is facilitated gently and mindfully. It is important we allow time for them to grasp the Prototype’s holistic model and processes, for their UPI to gestate, and for two fragile social systems (Prototype and group) to adapt to each other and reach the equilibrium necessary for them to operate effectively together.

5. Activating and sourcing capabilities in response to UPI requirements. When the group ‘feels’ sufficiently clear about their UPI, they are given the opportunity to conduct a Pilot within the Prototype.

The Community participates in related decision-making with openness and humility, seeing each UPI as an opportunity to learn and expand our own capacities. Mindful efforts are made to ensure that development is always under the direction of the group, and that our role remains that of a receptive enabler: sourcing and contributing specialism, materials and encouragement in response to the Pilot’s prevailing needs.

6. Helping realise the UPI through ongoing on-the-ground and virtual support. Upon completion of a successful Pilot, the group returns to their city or town to implement their UPI. By this time, they are equipped with ‘blueprint’ and experiences of a working Viable Alternative, and the skills to bring forth their own unique interpretation by transforming their local urban environment.

Throughout the realisation of their UPI, we continue to provide moral, specialist and financial support, and a sanctuary for retreat, review and restoration in the face of setbacks and systemic resistance.

UPIs are never colonies or subsidiaries, but rather lateral extensions of an expanding, highly interdependent Learning System. This emergent ‘Viable Alternative in action’ is held together by mechanisms that reinforce interrelationships: ritual gatherings where intent, principles and values are collectively reviewed, work and insights shared, and fun had. In the interim there are ‘dovetails’ – members whose role it is to participate in the decision-making processes of two constituent groups, thus facilitating the continuous flow of social learning through the whole system .

Although language may have represented this Action Plan as a linear sequence of stages, it was conceived as something more dynamic, reflective and feedback-driven, better captured visually in the Conceptual Model below.

And so ends our look at a possible ecology for a Prototype Viable Alternative, and an Action Plan for how it might seed nationwide transition bottom>up, inside>out and city>rural by way of an emergent Learning System.

To conclude this installment, possibly the most notable characteristic of the Action Plan on face value (particularly, one designed by a group of stakeholders operating at the leading-edge of sustainable development) is its humility. Perhaps when the scale, complexity and uncertainty of the challenge we face is spread across a wall for all to see, the only reasonable response is to design a system that acknowledges its own ignorance, creates the future one step at a time, and builds collective experience, reflection, experimentation and endeavour into its core DNA?

We hope you’ll join in a fortnight for Part 2, when we shall be exploring the four major themes that pervaded and informed the discussion of the Action Plan.

What I Learned from Destroying the Universe

Happy New Year! Arkadian’s first blog of 2013 is a brief account of a recent, and surprisingly meaningful, personal experience of a natural system, and the important lessons learned.

Over the Christmas holidays, during a rainstorm, I took the dog for his usual walk in a local wood. En route there’s a place where I bridge a stream on a fallen tree trunk.

Halfway across, something caught my eye. Hovering above the swollen and fast-flowing water, was a perfect Giotto circle, white, saucer-sized. I got down on my belly for a closer look. It was an exquisite ‘universe’ of tiny bubbles, revolving clockwise peacefully, seemingly oblivious to the mayhem surrounding it (I didn’t have my cameraphone, so other ‘attractors’ this universe called to mind will have to be used instead for illustration. There is also a short video of a similar phenomenon at the end).

For 45 minutes I lay spellbound, trying to discern the dynamics underpinning its beautiful form and behaviour. Immediately, upstream a large rock, barely breaking the surface, split the current into three highly erratic patterns: a fast and a slow channel, and another that surged over the top in intermittent waves. These flowed either side of the universe and beneath it, respectively. Evidently, some eddy arising from their interaction was causing bubbles to organise as they did. But no matter how hard I studied, I couldn’t fathom how such chaos could have given birth to so elegant and serene an entity.

Eventually, my inner scientist could resist no longer. Reaching down, I put my little finger carefully onto the surface of the fast channel about a hand’s span from the edge of the universe. Pft! In a moment it disintegrated into a million bubbles, swept downstream on the torrent.

I waited a further 15 minutes, expecting the universe to reform. However, although random associations of bubbles coalesced from from time to time, none maintained location or integrity for more than a few seconds before being washed away.

The dog was palpably exasperated by this point, so we resumed our walk but returned for another look on the way home. Nothing. Most days since, I’ve passed this spot. Never have I seen the universe again.

So what three important lessons did I learn from destroying the universe?:

1. That no natural system is inevitable. Half of me still can’t accept that so robust a phenomenon could have been an accident. The little universe played a trick on my mind such that it seems inconceivable the specific environmental conditions in that area of the stream would never have given rise to it or will not again at some point in the future.

My other half, however, is now deeply humbled by a new certainty about uncertainty. The only reasonable conclusion it can draw from an honest review of the sporadic serendipitous coincidences by which a natural system, such as the universe, evolves from anarchic molecular storms, is that Fate and Destiny are tales told in hindsight. Nothing is meant to be. This half finds the thought oddly comforting.

2. That no natural system is independent of its wider environment. My intervention was based on a long and careful assessment of possible interrelationships between the universe’s behaviour and environment. I deemed the touch of my pinkie sufficiently gentle and distant from the core system to cause, at worst, a tiny perturbation that might afford some penetration of its workings.

But the universe depended on a context much wider and richer than I could have expected. Even within my narrow scope of observation, this singular micro-dance between pattern and (apparent) disorder defied any linguistic, mechanistic or mathematical generalisation.

That it also depended on the outlying point in the stream at which my finger interposed, however, drew my puny mind flailing into all the other dynamic factors vital to the universe’s becoming – the bubbles’ surface properties, the woodland shelter, the upstream topography, the rainfall intensity, the climatic pressure, and so on, inwards and outwards into a matrix of wholly interdependent and nested systems.

One can only quake in awe at the complexity, and in terror at the hubris of a culture that imagines it can reduce and conquer such prodigious abundance. The Modern Self thinks itself independent of its world and, thus, perceives the pieces of its world similarly: believing each can be treated in isolation. These are suicidal delusions it would do well to wake from.

3. That one shouldn’t be fooled by the apparent stability of a natural system. Although I never expected the universe to endure forever, its superficial calm, autonomy and resilience in relation to its riotous milieu communicated a permanence that would easily tolerate some interference. This was an illusion born from ignorance. The merest touch of my finger was all it took to disturb some hidden, fundamental control parameter, and initiate a total irreversible breakdown.

To summarise, it is my view that the universe was an impossibly fortuitous, complex, and mysterious accident (this includes my own ability to contemplate it). The illusion that I was separate from it, had mastery over it, and could assume its stability based on appearances alone was a recipe for disaster. The same assumptions likely hold for all natural systems, including the biosphere of the Earth.

What I learned from destroying the universe is that the wisest approach for humankind is to cultivate a new personal humility and responsibility towards the natural systems we experience every day: to intervene in their unique, context-specific lives with mindfulness and empathy, and to seek a partnership that follows their lead in all things. We have so much to learn.

We hope you’ll join us in a fortnight for our first major series for 2013: a model for seeding a nationwide viable alternative to the current economic system (co-created by a team of PhD candidates focusing on sustainable development).

*Since writing this blog, Arkadian came across a similar phenomenon in another stream, and this time took a video (see below). Whilst the current and context is radically more sedate, the behaviour is in many ways very similar to the instance described above and offers a good illustration.

Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

Welcome to the belated final installment of our five part analysis. We have been working towards the title’s conclusion by seeking an answer to the following question.

What difference between natural / social, and economic, systems causes one to tend towards diversity and stability, and the other, uniformity and instability?

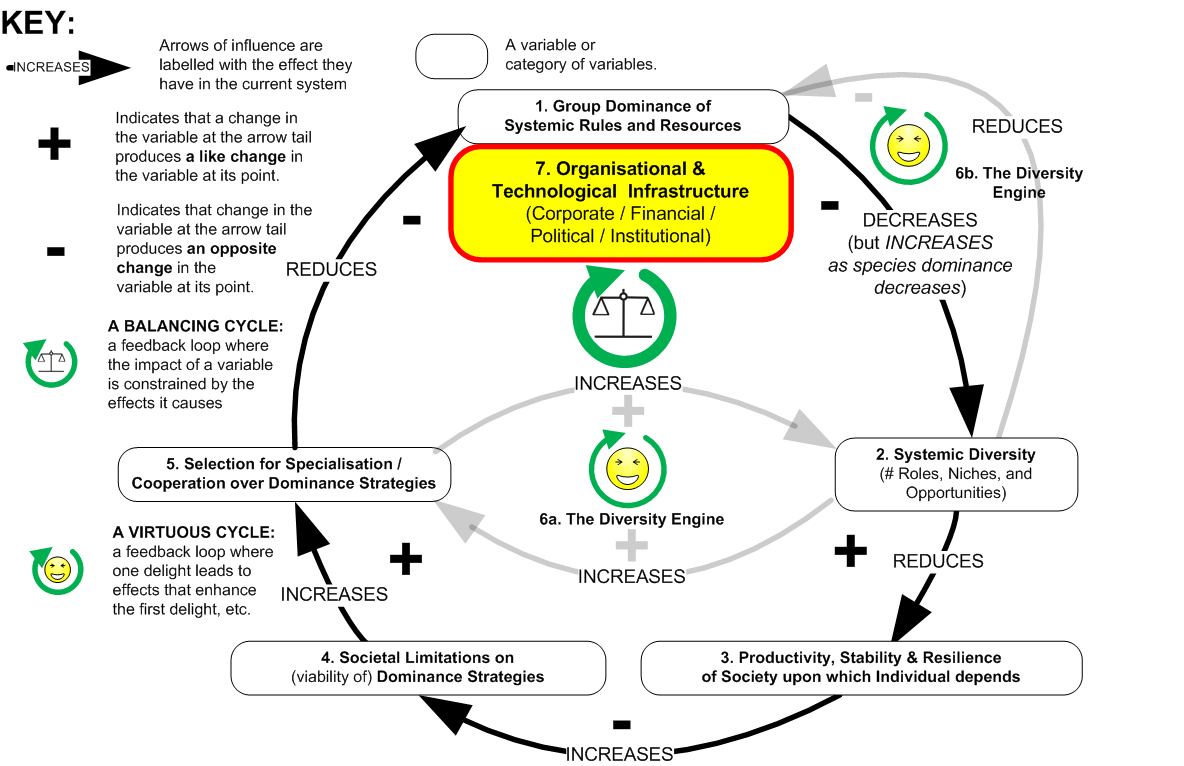

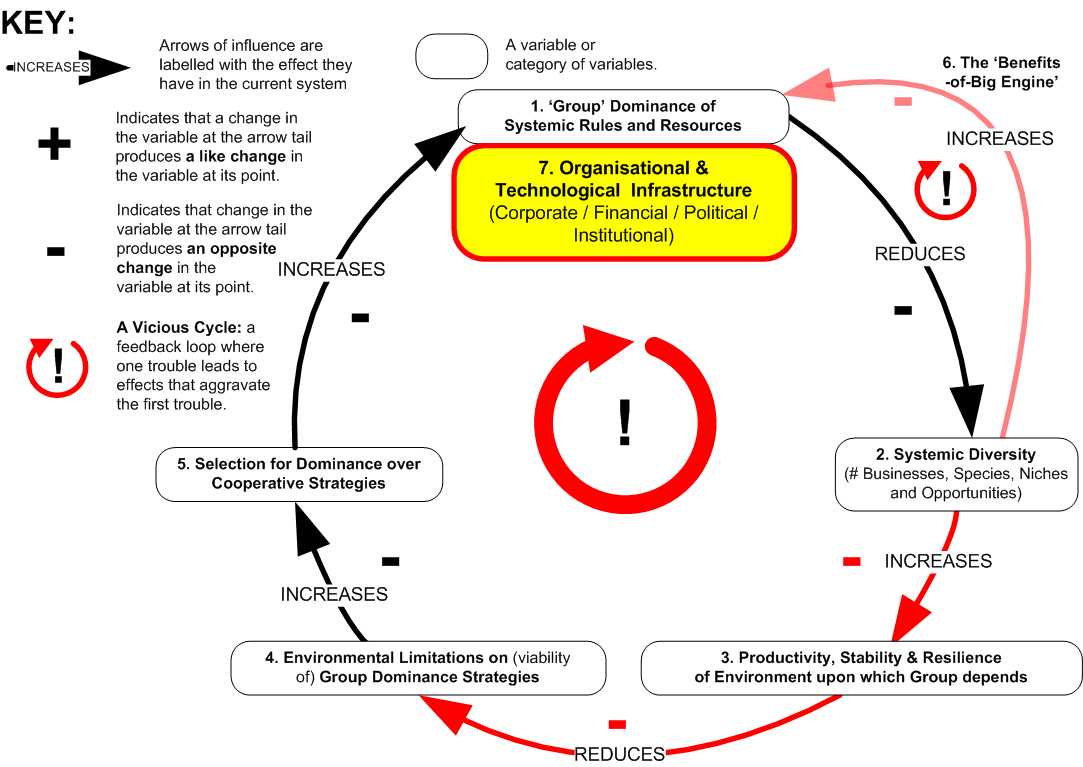

In installments 1, 2 and 3, we proposed that in natural / social systems a species or ‘group’ seeking total domination of their environment are constrained and, ultimately, destroyed by the impoverishing and destabilising effects of their actions on the systems upon which their own survival depends, thus leaving the arena open for dynamics that promote diversity and long-term stability (see previous installments if you need an explanation of the model below).

In installment 4 we suggested that the current economic system displays a reverse trend towards uniformity and instability because it allows the small ‘groups’ at the helms of corporations to gain increasing wealth and power from disintegrating social / natural systems without ever personally experiencing the environmental backlash of their actions. (see installment 4 if you need an explanation of the model below).

To clarify, this shouldn’t be taken as a demonisation of businessmen. Some individuals are naturally entrepreneurial, status-driven or materially-oriented, and the prosperity and order we have come to enjoy in recent centuries are largely indebted to their spirit and energy. Indeed, there are few among us that wouldn’t pass up a lottery win and the prestige, security and freedom it affords.

To clarify, this shouldn’t be taken as a demonisation of businessmen. Some individuals are naturally entrepreneurial, status-driven or materially-oriented, and the prosperity and order we have come to enjoy in recent centuries are largely indebted to their spirit and energy. Indeed, there are few among us that wouldn’t pass up a lottery win and the prestige, security and freedom it affords.

However, in the current era, unconstrained profit-and-power motivated vicious cycles represent a mortal threat to our freedom of choice, quality of life and, most urgently, our planet’s life systems. If the virtuous feedback mechanisms that promote diversity and stability in natural / social systems do not function naturally in the current economic system, then they they must be imposed artificially with due haste. But how?

First let’s summarise, in a nutshell, the problem to be resolved…

In the current economic system, dominant ‘groups’ are able to benefit from abusing the diversity and stability of socioenvironmental systems without ever experiencing negative feedback from their actions.

Although many possible interventions occurred to Arkadian whilst writing this series, a coherent regulatory model, which offered an unobjectionable, easy transition from the current economic system was not so easy to imagine (the reason why the final installment has been so long in coming!). Happily, a fully-formed (40yr old) solution presented itself recently in Chapter 19 of ‘Small is Beautiful’, courtesy of the genius of economist, E.F. Schumacher (pictured left).

The Schumacher Business Model, stated simply, rests on 2 systemic ‘tweaks’: (1) limiting the number of people a single corporate entity can employ and (2) introducing meaningful public ownership and accountability into business structure and practice.

(1) Legally restricting corporation size by number of employees. It would seem reasonable that a ceiling should be dictated chiefly by evidence regarding effective human group size (see Dunbar’s number), say between 80-200 persons. Growth beyond the upper limit, Schumacher suggests, should entail the formation of new independent corporate units, which may be linked by joint stock. These restrictions would enable each employee to ’embrace the idea of the business as a whole’ and the value of their role therein, but most importantly to the current argument, it would ensure that ‘the group (i.e. The Board)’ couldn’t claim ignorance of the details of their company activities and, thus, could reasonably be held personally accountable for abuses.

Furthermore, constraining size, particularly when the exploitation of natural / social resources is involved, is also more likely to physically ground a corporation in a local environment. Bringing ‘the group’ closer to their employees and the raw coal face of their realworld transactions is likely to increase their susceptibility and responsiveness to negative socioenvironmental feedback both internal and external to their organisation. It is also liable to curb the scale of impacts of which a single corporate vehicle is capable.

All very well, the cynics may cry, but what of the ‘groups’ with the thicker skins and thinner moral fibre?

(2) Public Ownership and Accountability. Schumacher advises we put an end to annual corporate taxation (a proposition not disagreeable to most businessmen!). In its place he proposes that for every share sold privately by a company, a further share is issued to the public. Thus, as owner of 50% of the company, we’d collectively receive half of any dividends if and when they are paid out to shareholders (he argues that when a company grows beyond a certain size it loses its ‘private and personal character’ and thus can be considered, in a sense, a public enterprise anyway).

To avoid disruption, our public equity wouldn’t allow us any voting rights in everyday business decision-making. It would, however, entitle us to attend Board meetings as an observer and, if the actions of the business were deemed to run counter to the public or environmental interest, we could apply to a court to get dormant voting rights activated.

To avoid disruption, our public equity wouldn’t allow us any voting rights in everyday business decision-making. It would, however, entitle us to attend Board meetings as an observer and, if the actions of the business were deemed to run counter to the public or environmental interest, we could apply to a court to get dormant voting rights activated.

To exercise these corporate responsibilities, Schumacher proposes the creation of independent citizen bodies funded from local business dividends. These ‘Social Councils’ would be split into four equal parts: three would have their members nominated by local trade unions, professional, and environmental, organisations, with the final quarter being drawn randomly from local residents in the manner of jury service. Involvement in management processes would, of course, be bound by strict confidentiality agreements.

Schumacher’s model brings socioenvironmental feedback directly into the Board room both as a ‘possibility in the background’ and, when necessary, as a real, prevailing constraint.

It is Arkadian’s prediction that, over time, exposing the ‘groups’ at the corporate helm to these balancing dynamics would drive a new trend towards macroeconomic diversity and stability, and greater corporate responsibility for the integrity of the natural environment (by triggering the ‘Diversity Engine’, described in installments 1, 2 and 3). And to top it all, it would require minimal design and economic / legal restructuring because, in the main, the model utilises existing frameworks and practices.

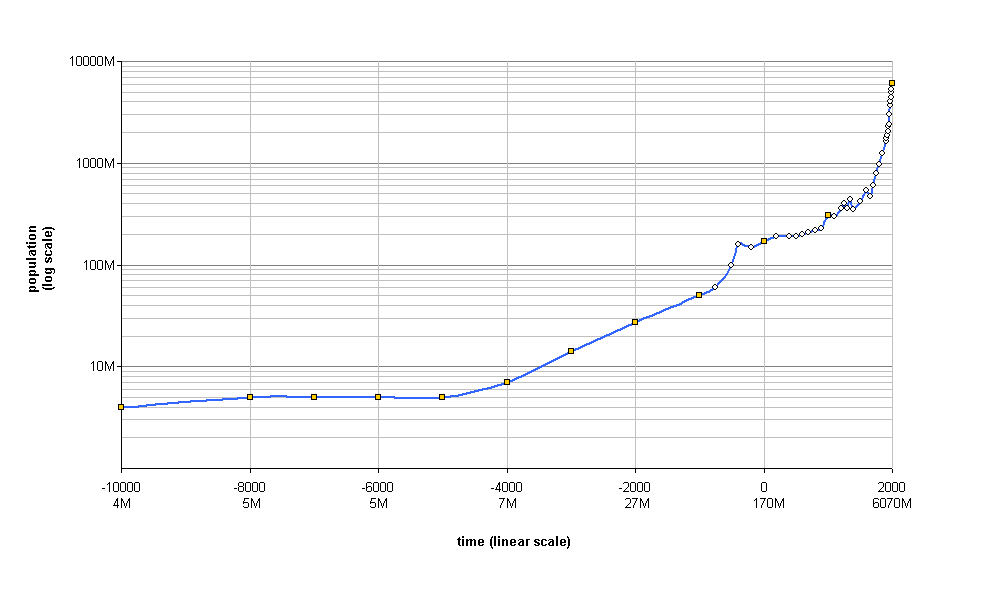

To conclude, effective corporate regulation is not just a Utopian nice-t0-have. It took till 1960 for World Population to hit 3bn. It has grown by 1bn approximately every 12yrs since, probably hitting the 7bn mark earlier this year. There are more human beings to house and feed today than have ever lived before. Presently, we have just over 2 acres of workable land each, 4x less than a century ago, and this is shrinking each moment as corporate activities and climate change destroy the natural world, and population continues to skyrocket.

Resultant biodiversity loss, whilst often second-ranked in current ‘problem’ trends is, as we’ve established, probably the most dangerous of all due to its inscrutable relationship with macroenvironmental instability. With extinctions currently at 1000x the background base rate, and predicted to rise to 10,000x over this century, we are very rapidly, and very blindly, removing the Jenga pieces of our life systems, largely for the sake of the short-term wealth creation of the small ‘groups’ of the corporate elite. History is littered with exemplars of total societal and environmental meltdown as the result of human impact on vulnerable ecosystems: Easter Island, The Mayans, The Pueblo Culture of the South Western USA, the Norse Greenland and Iceland colonies to name but a few. If we repeat the same mistakes globally, we may not get a second chance.

Resultant biodiversity loss, whilst often second-ranked in current ‘problem’ trends is, as we’ve established, probably the most dangerous of all due to its inscrutable relationship with macroenvironmental instability. With extinctions currently at 1000x the background base rate, and predicted to rise to 10,000x over this century, we are very rapidly, and very blindly, removing the Jenga pieces of our life systems, largely for the sake of the short-term wealth creation of the small ‘groups’ of the corporate elite. History is littered with exemplars of total societal and environmental meltdown as the result of human impact on vulnerable ecosystems: Easter Island, The Mayans, The Pueblo Culture of the South Western USA, the Norse Greenland and Iceland colonies to name but a few. If we repeat the same mistakes globally, we may not get a second chance.

Considering the twin pincers of population growth and biodiversity loss, it is quite evident that socioenvironmental stability and sustainability are our most important objectives for the c21st, bar none. Our very survival depends on achieving them and success is contingent upon economic and environmental policy which is underpinned by the principle of diversity=stability=good. If variety is both the spice and source of life, then we must put democratic pressure upon Government and business to make the small tweaks to our economic system necessary for it to produce abundance by its own workings.

For a fascinating and vitally important lesson in the importance of preserving and promoting biodiversity, Arkadian cannot recommend the video below more highly. Essential viewing for all inhabitants of Planet Earth.

The Root of all Evil: how the UK Banking System is ruining everything and how easily we can fix it.

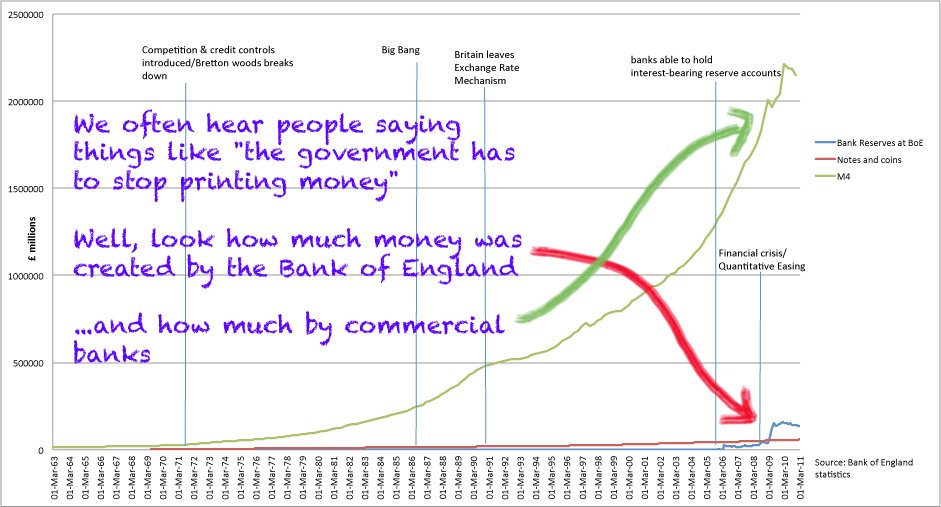

Whilst no economics ‘expert’, it has become clear to Arkadian from evidence presented by organisations such as Positive Money and the New Economics Foundation that the UK Banking System is (i) rapidly driving us into a new Dark Age and (ii) not nearly as difficult to understand as those with a vested interest in it would have us believe.

As positive change depends on a general understanding, the current article aims to compare, in simple terms, how this system has worked in the past, and should work, and how it works currently to the detriment of you, your children, your community and your future.

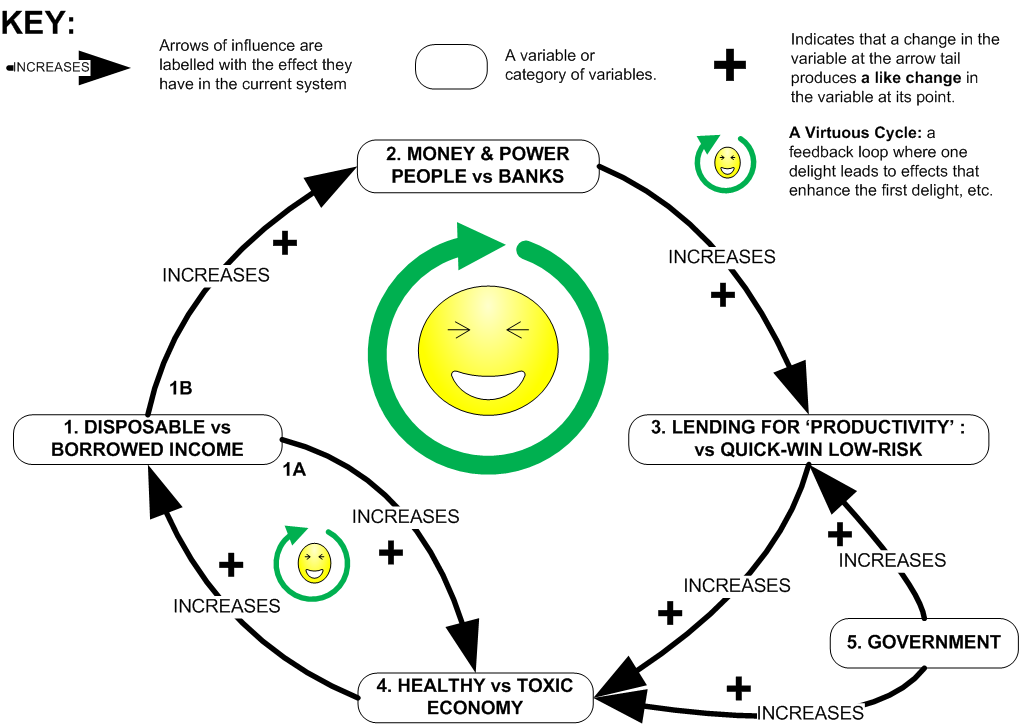

HOW IT WORKED (THE VIRTUOUS CIRCLE):

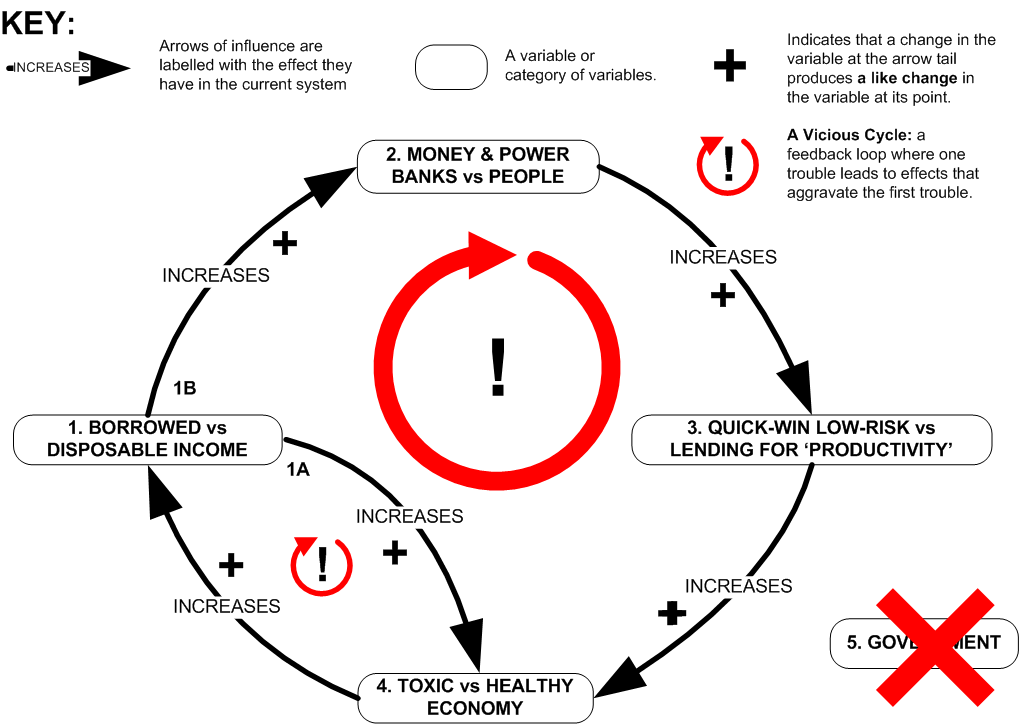

To begin, lets look at a diagram of how the UK economy worked in the years following WWII. At that time the country, as now, was stone broke but, unlike now, was driven by people-centred values sharpened in response to the Axis Power’s policies of dehumanisation. It is also a model of a ‘classic’ Capitalist System, as described by Adam Smith. Most people, and politicians, still mistakenly believe it works this way.

The arrows represent the flow of money, and the boxes: important ‘variables’ in the system. You can start anywhere, but it’s probably easiest to start with the box to the left.

1. Disposable vs Borrowed Income. You made a decent living in a secure job-for-life that allowed plenty of free time for friends and family. Your mortgage aside – which took around 10-15yrs max to pay off – you only bought things if and when you could afford them, thus putting money back into ‘circulation’ (arrow 1A). The remainder went into your savings account or share investments (arrow 1B) …

2. Money and Power: People vs Banks. …Banks were dependent on your savings to function as they were only permitted to lend in relation to their cash reserves. Their business worked by making money from the interest on these loans…

3. Lending for Productivity vs Quick-Win Low-Risk…As banks were still very much focused at a High Street level, much of their investment went into small businesses…

4. Healthy vs Toxic Economy…Thus your savings helped foster a growing, diversifying and stable local economy, which meant more secure jobs and, coming full circle, (1) more disposable income for other people to spend or save as well as a range of other social benefits associated with greater income equality.

5. Government, meanwhile, ‘governed’ the system to ensure it worked properly. In partnership with the Bank of England, they monitored the economy, periodically injecting new printed cash into the system to fill the ‘gap’ created by new growth, via public services that safeguarded citizens’ life dependencies (energy, social security, education, policing, health, telecoms, transport, postal service, military) and provided reliable employment for millions. They also regulated the banks to ensure they lent justly and responsibly.

And so it worked, by no means a well-oiled machine but still one guided by principles of fairness, general well-being, and economic restraint. So what’s changed?

HOW IT WORKS NOW (THE VICIOUS CIRCLE).

1. Borrowed vs Disposable Income. Whilst you (unlike many) may still make a decent living, you and your partner work doubly-hard out of fear of losing your jobs and being unable to meet your mortgage and debt repayments.

In your absence, your children are raised largely by others. Even when you’re home, it’s tough to find energy for them when what you need is relaxation from the stresses and strains. The cost of a property sufficient to comfortably house your family has meant you’re probably destined to spend your whole life surviving on credit and without savings…

2. Money and Power: Banks vs People…But isn’t ‘no savings’ an issue for the banks? Not anymore! Now, when you need to borrow, they are free to tap the number into a spreadsheet and create it for you out of thin air, irrespective of the amount of ‘savings’ in their reserves (arrow 1B) . They also decide your interest rate: the ‘money-for-nothing’ (quite literally) from which they’ve grown rich, politically-powerful and monolithic…

3. Quick-Win Low-Risk vs Lending for Productivity…And these global giants no longer have time for long-term, high-risk investment, such as small or ‘ethical’ businesses. They plough your ‘interest’ into quick-win low-risk high-return investments, which are safely recoupable should anything go belly up.

Around 90% goes int0 speculation, contributing virtually nothing to the economy, and, in the case of the food and currency markets, causing the suffering and deaths of millions in poorer countries. Much of the rest goes into property, and loans to big corporations that value short-term profit over the welfare of planet and people – fossil energy, mining, factory farming, mass media, consumer goods, processed food, the military etc.

4. Toxic vs Healthy Economy…Although in good times the economy appears to grow, growth no longer signifies health. Property prices inflate beyond the reach of many: notably, your descendants. Private monopolies supplant public services and local business, and we become increasingly dependent upon them for life essentials, employment, and a functional economy…

5. Government… So where are they in all this? Precisely! As mentioned in (2.), they’ve handed over the lion’s share of the responsibility for creating and managing the nation’s money to the financial sector. They’ve also permitted a few banks, and other monopolies, to grow so large and powerful that political success now hangs upon prioritising their interests over those of their electorate (with over half of Conservative Party funding now reliant on the banking sector and much of the remainder coming from defence, manufacturing and energy, is it any surprise that voter needs should come second to their sponsors’ return on their investment?) Whilst Whitehall may maintain the illusion of steering the British economy, technically they can’t because they’ve abdicated the controls.

And so the Vicious Circle turns, with each cycle the system becoming more unequal, uniform and unstable. There are three particularly vicious aspects of this system worth noting.

Firstly, it functions irrespective of recession. In boom, you borrow to get the things to which you aspire now rather than having to wait – using credit / store cards, bank loans, mortgages and the like – and the banks get rich and powerful. In bust, you borrow to make ends meet and the banks get rich and powerful.

Secondly, in a recession, because the vast majority of the money in the system is ‘borrowed’, to prioritise the repayment of the bank-invented debt (i.e. ‘Austerity’) over strategies for stimulating spending is guaranteed to shrink the economy further. Simply put, if pennies are taken out of the national purse and vanish into thin air without any being put back in, there will be less money in the purse. Unless, of course, we can find a bank to lend us a more.

Thus, whilst the historically-proven formula for economic recovery has always been to kickstart the Virtuous Circle through public spending and corporate regulation, in this sick misshapen world, crashes, austerity, privatisation and price hikes are great because they force us to borrow more, which indirectly results in new ‘imaginary’ money getting injected into the economy (arrow 1A).

And although a life of indebtedness for food, housing, clothes, education and so on, may promise an increasingly bleak existence for us and our children, for the environmentally-unconscious one-stop corporate shop that creates our credit, charges our interest, employs us as temps at the minimum wage, and is the only place where we can buy anything, it’s a field day.

Lastly, the unsustainability of this rampant money creation is largely irrelevant to the banks because, ultimately, the public debt is underwritten by the Bank of England, in other words, US! You, yes YOU, are effectively part-guarantor of everybody’s loan, including your own. The bubble will always burst, and more spectacularly each time, and it’ll always be you that is liable for the debt, never those that made billions from the recklessness.

Happily, fixing the system is remarkably simple. You have two choices. The easiest is to pick up the phone and (1) MOVE YOUR MONEY out of the Vicious Circle and into an ethical bank such as The Coop or Triodos, who maintain a responsible lending policy, consult you on your ideas for a better future and invest in them – organic farming, renewables, community development and so on – rather than whatever horror brings in the profits. Do it now and enjoy looking your children in the eye with a clear conscience!

(2) is to PUT PRESSURE ON YOUR GOVERNMENTAL SERVANTS to re-impose the vital framework that regulated the Virtuous Circle.

Most critically, this means returning the responsibility for money creation to The Bank of England. Exercise of this responsibility should involve the immediate injection of real cash into circulation (‘quantitative easing’) via investment in a growing public sector and green transition. This would reduce our economy’s toxic dependence on debt to function, generate employment and spending (the only way out of recession), and begin the change upon which a tolerable future hinges.

Close second, however, involves excising the corporate influence from our political system and allowing the democratic needs of citizens to determine Governmental decision-making, and not the insatiable greed of a small commercial oligarchy.

Thirdly, the ‘ecology’ of the financial sector should be regulated so that a significant percentage of banks are always focused on investment at the local level. This is the approach in Germany, and the greater diversity and stability of their banking system has enabled them to weather the present storm significantly better than most.

In short, if you wish to remain in a world where you are dependent on corporate monopolies for your existence, and where the conditions of your life and planet are certain to deteriorate, then sit back and do nothing. However, if you’d prefer a return to a financial system that works towards the common good then MOVE YOUR MONEY NOW!

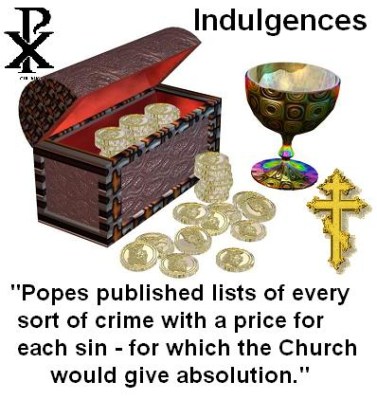

A concluding thought: in The Early Middle Ages we were told the Bible was only comprehensible and communicable by The Church. It was a tale that, for a considerable time, maintained vision, interpretation, practice and power in the hands of an elite few.

Arguably, the translation of the Bible from Latin into English and its popular dissemination was one of the driving forces behind the development of the more market led and equitable society of later centuries. Knowledge, as they say, is power.

In the c21st our ‘mystery’ is The Economy, our priests: the politicians, economists and bankers. Pah! Economics is easy, isn’t it? It’s just about how we can make money work best for us and our loved ones.

So go on: inform your friends and family. Ask them to move their money too. It’s time to debunk the ‘priesthood’ and reclaim control over our lives, planet and future. Forever and ever. Amen!

Want to know more? Arkadian highly recommends following Positive Money or the New Economics Foundation on Facebook, or watching the illuminating video below. Learn and share!:

What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

This article is about a ‘whole systems thinking’ session Arkadian ran with 15 Occupy followers of all ages and backgrounds. All participants were required to answer 3 questions: –

(1) What is Occupy’s purpose; (2) How should this purpose be achieved and; (3) Why was it important?

Personal thoughts were written on post-its, stuck on a wall, and organised by the group according to content similarity and difference. The discussion fueled by these activities gave rise to 6 collective insights (the 7th is an insight Arkadian derived from the others): –

(1) Occupy is a grass-roots, direct-democratic movement

(1) Occupy is a grass-roots, direct-democratic movement

(2) Occupy is ‘about’ co-creating and enacting a Viable Alternative to the current system

(3) The Viable Alternative is a collective vision

(4) Achieving the Viable Alternative requires building critical mass

(5) Building critical mass depends on making the Viable Alternative simple, relevant and clear to the wider population

(6) Aims could be best achieved through grass-roots ‘campaigns’ connecting the Viable Alternative to local community issues

(7) These insights had implications for Occupy’s organisational design

There follows a brief explanation of each: –

1. Occupy is a grass-roots, direct-democratic movement: All followers saw Occupy as ‘of the people / for the people’, independent of, and transcending all, other organisations. There was genuine concern that ‘partnerships’, or Occupy chapters becoming formal or political entities, would compromise the essential qualities of this idea. Nevertheless, it was also acknowledged that high profile support could, and had, delivered some powerful PR.

The solution proposed was that ‘partnerships’ should always be one-way and arms-length only, i.e. limited to inviting, or allowing, third parties to sign up to Occupy’s (viz: ‘the people’s’) aims and principles. But what aims and principles?

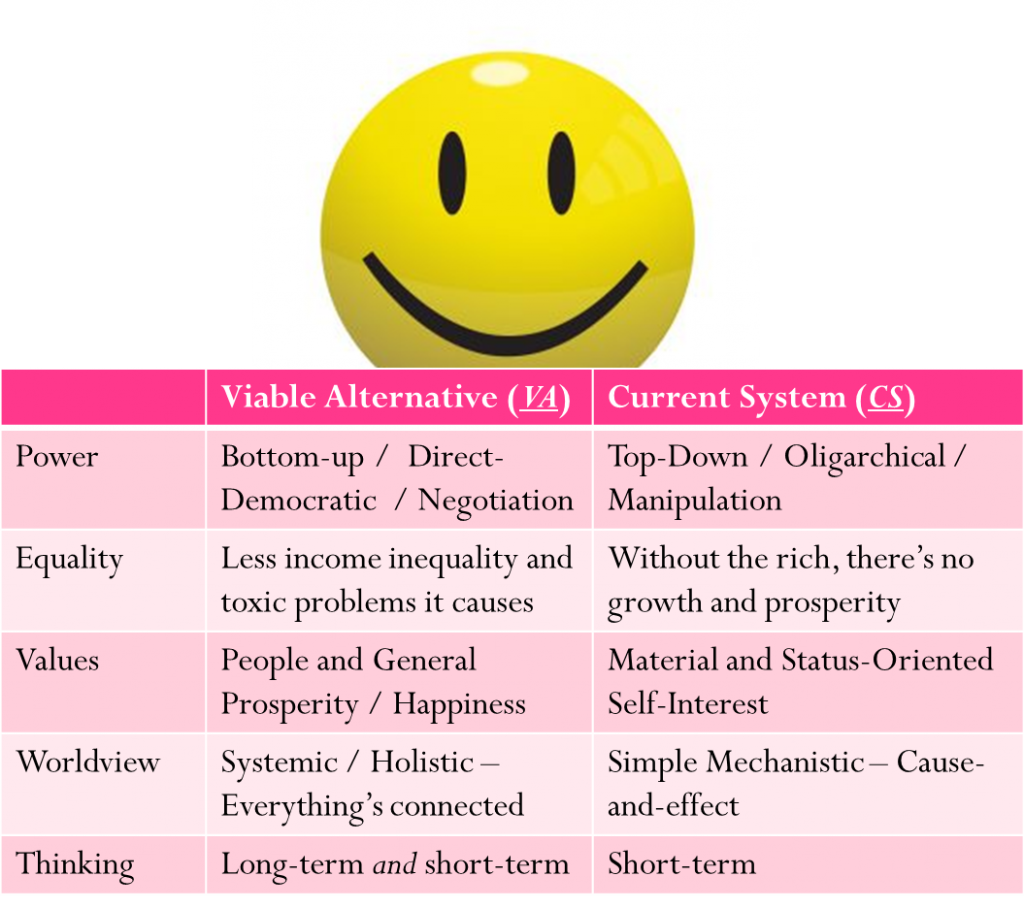

2. Occupy is ‘about’ co-creating and enacting a Viable Alternative to the current system: The most powerful theme that emerged in the discussion. To get a handle on some of the structural principles of this Viable Alternative, ask yourself the following questions…

Power: Would the world be better if people had greater involvement in decisions that affect their lives and future?

Equality: Would the world be better if the gap between rich and poor were reduced? (N.B. Not to a ‘ Communist’ extreme, merely a lessening of the vast multipliers separating high / low incomes and developing / developed nations, and their toxic impact on society and environment).

Equality: Would the world be better if the gap between rich and poor were reduced? (N.B. Not to a ‘ Communist’ extreme, merely a lessening of the vast multipliers separating high / low incomes and developing / developed nations, and their toxic impact on society and environment).

Values: Would the world be better if quality of life and well being were valued over material and status-driven self-interest?

Worldview: Are the big social, environmental and economic challenges connected in any way? Might addressing one have beneficial effects on others?

Thinking: Should the well being of future generations and the long-term viability of life on our planet be important to current decision-making?

If you answered ‘Yes’ to any, or all, of these questions then you’re ‘Occupy’. Below is a rough summary table comparing the principles of the Viable Alternative to those of the current system.

So what actions does all this imply? Firstly, if they are widely shared, then these structural principles could provide the ideal framework for coherent organisation, action and communications, and solidarity, across diverse contexts.

Secondly, the Viable Alternative is a positive idea: it’s about a happier, better future. Whilst its necessary to highlight why change is necessary, negative news and arguments about the nitty-gritty can drive people away. Emphasising these higher-level, common and cheerful principles, on the other hand, could score greater successes with the wider population.

3. The Viable Alternative is a collective vision: The whole group shared a belief in the urgent necessity for the Viable Alternative, which in turn, seemed dependent upon an understanding of the scale and interconnectedness of the issues.

However, each individual held their own beliefs about what the important problems were, how they were connected, and the appropriate remedies and actions: a product of their life experiences, personal interests and, for many, exposure to new information since engaging with the movement.

Nevertheless, the post-its-on-the-wall represented a truly epic mess, one that evidently required highly situation-specific solutions, each of which defied the analytic or predictive capabilities of any ‘expert’. Recognition of this within the group seemed to drive processes where individual experiences were tools for building, negotiating and informing a dynamic picture of NOW, in order to decide the best next step(s) only, not the grand master plan.

Rather than disagreements about which view was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, all views seemed appreciated as valuable and partially right. In a sense, the group behaved like a ‘super-brain’, leveraging many lifetimes’ worth of perspectives, knowledge and experience to reach wise ‘objective’ assessments and decisions about an impossibly complex ‘subjective’ situation.

Rather than disagreements about which view was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, all views seemed appreciated as valuable and partially right. In a sense, the group behaved like a ‘super-brain’, leveraging many lifetimes’ worth of perspectives, knowledge and experience to reach wise ‘objective’ assessments and decisions about an impossibly complex ‘subjective’ situation.

So what are the implications of all this? Firstly, if collaborative decision-making can be so individually empowering and collectively clever, then all Occupy followers should be furnished with simple group moderation skills and ‘whole systems’ tools. Processes that focus discussions on external representations (pictures / post-its / models etc.) should become a sine qua non of the movement.

Secondly, the movement should stress that, whilst expressing a personal view is the inalienable right of any follower, unless its braided into a collective decision, it ain’t Occupy!

Lastly, if action is motivated by seeing the connections between disparate social, economic and environmental issues, then Occupy should underscore ‘stories’ that highlight the ‘connections’, and fast track new members into contributing to collective decision-making – judging by the discussion, it’s difficult not to ‘join-the-dots’ when exposed to the Occupy ecology.

Lastly, if action is motivated by seeing the connections between disparate social, economic and environmental issues, then Occupy should underscore ‘stories’ that highlight the ‘connections’, and fast track new members into contributing to collective decision-making – judging by the discussion, it’s difficult not to ‘join-the-dots’ when exposed to the Occupy ecology.

(4) Achieving the Viable Alternative requires building critical mass: Reflection upon this fact led rapidly to the recognition that human and financial resources were critical priorities, and that there were probably no shortcuts to them.

(5) Building critical mass depends on making the Viable Alternative simple, relevant and clear to the wider population: The second dominant theme of the session. To successfully engage the wider population, it was deemed Occupy needed communications that were simple, relevant to the differing needs of specific target audiences, and employed clear popularly-understood terminology pitched at the appropriate level of understanding, e.g. stock phrases like ‘socioeconomic justice’ and ‘ecological limits’ were not understood by many in the group. It was also considered important that these messages were backed-up by incontestable evidence and sources, and communicated solidarity.

Everyone also acknowledged this would entail outwitting the ‘guardians’ of the current system ‘at their own game’, exploring channels that they don’t, or can’t easily, command, and responding quickly and devastatingly to opposition. The discussion highlighted that intelligent, reflective information management – researching, screening, organising, tailoring – was central to Occupy’s role and ultimate success.

So, to recap. Occupy needs to…

(i) Organise without being an organisation.

(ii) Communicate a Viable Alternative when no-one can know what it is, and where it is only made manifest via specific situations and perspectives.

(iii) Create an outward appearance of solidarity when structured disagreement is an essential requirement.

(iv) Use channels not covered by the ubiquitous guardians of the current system, whilst building volunteers, funds and critical mass.

What solution to these challenges did the collective propose?

(6) Grass-roots ‘campaigns’ connecting the Viable Alternative to local community issues: Explore and discuss ‘issues’ door-to-door. Those that resonate, have local relevance, and are aligned with the Viable Alternative could then become the focus of grass-roots campaigns, building to direct ‘visible’ action, and all informed by Occupy’s structural principles, particularly, inclusive community decision-making. Not talking and blaming, but showing the world how things could be: through small-scale collaborative achievement and learning.