Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

Hello again and thanks for joining us for the second in a five-part Arkadian analysis, where we show how we reached the conclusion of the title series by way of one simple question: –

“What difference between natural / social systems and the current economic system causes the former to tend towards diversity and stability, and the latter, uniformity and instability?”

Last week, we explored why natural systems tend towards diversity and stability. Dynamics were proposed (the ‘diversity engine’) that, through natural selection, weed out species that strive for environmental supremacy and favour those that cooperate, specialise and, by doing so, facilitate opportunities for new evolutionary adaptations.

This week we shall take a brief look at one creature that, at first sight, appears to operate outside these dynamics: Homo Sapiens. What is it about the human species that enables it to dominate ecosystems without appearing to suffer the constraining feedback?

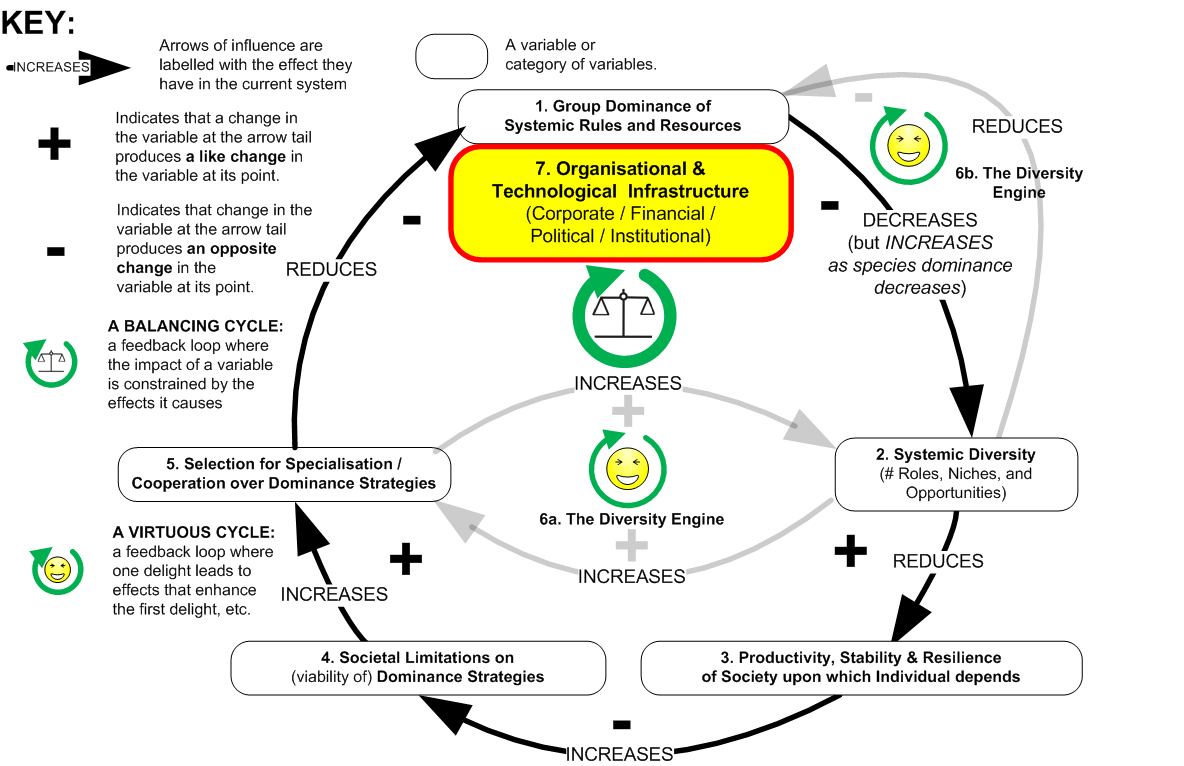

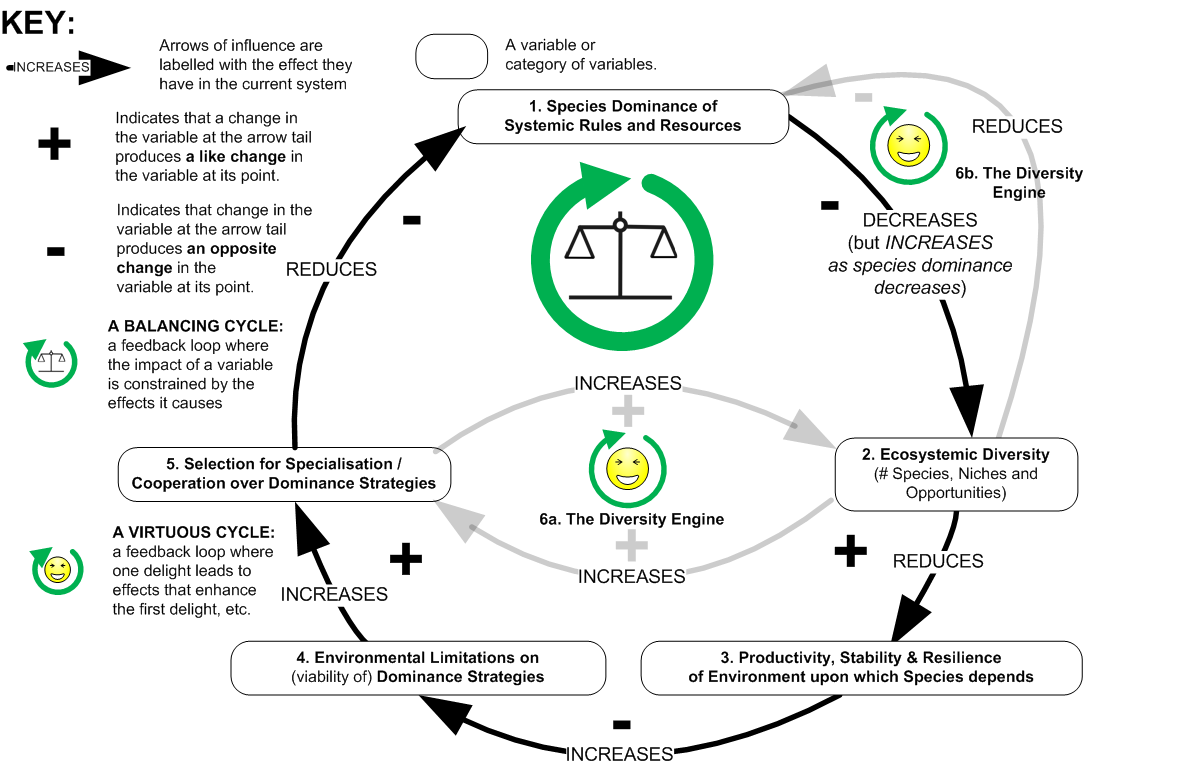

MODEL 2 of our analysis below proposes an answer (N.B. If you have trouble reading the text, click on the diagram to open it in a new browser tab and then refer back to the explanation here).

If you joined us last week, you’ll see immediately that MODEL 2 is more-or-less identical to MODEL 1. We propose that civilisation’s social matrix shares the same stabilising dynamics of natural systems and that these confer the ability to adapt more reflectively and effectively to environmental constraints.

Significantly, world population only began to increase appreciably with the order provided by the first civilisations from around 1,000 BC onwards. Many historians argue that the political infrastructure of Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, India and China initially emerged from local organisational efforts to coordinate large scale (particularly, irrigation) ecosystem management, rather than these projects being the initiative of an already-ensconced ruling ‘group’.

It is the Arkadian view that the managerial perspective born from these projects enabled infrastructural and organisational tweaks that, in turn, facilitated a trend towards increasing division of labour and role / skill / knowledge specialisation, and it was this burgeoning socioeconomic diversity and interdependence rather than the direct actions of a ruling group that provided the stability required for civilisation to flourish.

Indeed, as many power / status / wealth hungry ruling groups have since discovered to their own detriment, enduring political success hinges not on their own genius, but on the assiduous maintenance of this diversity engine. As a general rule (and as with the overbearing species we looked at last week), (1 and 2) the greater the impact of the ‘group’s’ rule and resource dominance on local socioeconomic (and environmental) diversity, (3 and 4) the more unproductive, unstable and weaker their regime tends to become.

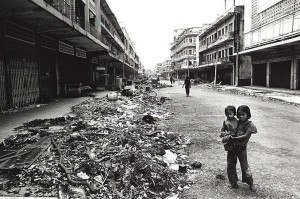

A tragic example of this self-defeating governmental dynamic is Cambodia under the communist Khmer Rouge. Seizing power in 1975 in the wake of 4yrs of destabilising bombings by US and Vietnamese forces, they immediately shut down all transport and information links with the outside world, declared private property illegal, and established a ‘Year Zero’ for Cambodian society.

Their ‘Agrarian Revolution’ – an economic model founded on the single pillar of self-sufficient rice production – was to have a cataclysmic impact on all aspects of systemic diversity: social, cultural, economic and environmental.

Their ‘Agrarian Revolution’ – an economic model founded on the single pillar of self-sufficient rice production – was to have a cataclysmic impact on all aspects of systemic diversity: social, cultural, economic and environmental.

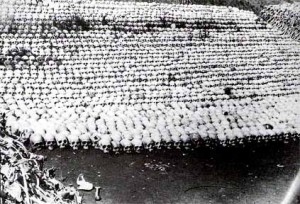

All those who threatened their ideological dominance were murdered or exiled – ethnic and religious minorities, journalists, doctors, educators, writers, anyone with an education – obliterating vital cultural, intellectual and skill resources.

Urban populations were forced to leave cities, towns and former roles behind to slash-and-burn virgin rain forest, set up collective farms, and take responsibility for rice production, whilst the thousands of male peasant farmers with the requisite know-how were press-ganged into military service.

Naive farming communities went hungry rather than risk retribution for failing to meet the Government’s exorbitant rice targets, which soon resulted in a precipitous deterioration in output. Almost a quarter of the population died of starvation or execution under the regime, a disproportionate number of which were male.

Naive farming communities went hungry rather than risk retribution for failing to meet the Government’s exorbitant rice targets, which soon resulted in a precipitous deterioration in output. Almost a quarter of the population died of starvation or execution under the regime, a disproportionate number of which were male.

Within three-and-half years, the loss of diversity and productivity had rendered the Khmer Rouge’s power base so weak, they were easily overthrown by a Vietnamese invasion.

30 years later, the Cambodian ‘system’ is still suffering. Political instability has resulted in 4 coups over the interim period. The country still has the highest proportion of women (65%), malnutrition and physical disability in South-East Asia (the latter attributable primarily to the Khmer Rouge’s estimated 4-6m unexploded mines).

The country’s economy remains dependent on tenant farmers involved in backbreaking rice production for minimum profit. Necessarily, many of these are women, creating further societal tensions by violating customary rules and roles of a traditionally patriarchal society. International development experts argue that, despite the potential for a full recovery, without external intervention the Cambodian socioeconomic system will struggle to escape the impoverished, fragile state in which it was left by the Khmer Rouge.

Conversely, ‘laissez faire’ ruling groups, such as The Ancient Greeks and Romans, that implemented policy and infrastructure which nurtured the (5/6) ‘socioeconomic diversity engine’ tended to produce history’s more enduring and resilient regimes. For example, in the mid c14th a nascent Western European civilisation – arguably, the most pluralistic, productive and market-driven the world had yet seen – successfully weathered a perfect storm of catastrophe that would have devastated a weaker social system, including climactic cold spells, famines, widespread peasant revolts, The Black Death, and an overall loss of quarter of the population.

Conversely, ‘laissez faire’ ruling groups, such as The Ancient Greeks and Romans, that implemented policy and infrastructure which nurtured the (5/6) ‘socioeconomic diversity engine’ tended to produce history’s more enduring and resilient regimes. For example, in the mid c14th a nascent Western European civilisation – arguably, the most pluralistic, productive and market-driven the world had yet seen – successfully weathered a perfect storm of catastrophe that would have devastated a weaker social system, including climactic cold spells, famines, widespread peasant revolts, The Black Death, and an overall loss of quarter of the population.

Nevertheless, (6b) although these ‘laissez faire’ strategies yielded prosperity for ruling groups, they also entailed a diminishing of their control over rules and resources as increasingly pluralistic and influential populations demanded ever greater democratic freedoms, rights and representation.

As we shall discuss in Week 4, this shift would ultimately give rise to a global economic elite whose power, and impact on diversity and stability, would dwarf that of any political ‘ruling group’. However, before we do, we thought it worth taking a moment to understand why it is that an ecosystem or ‘civilisation’ is more stable if it is diverse? Hope you’ll join us next Friday to find out.

Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 1 of 5: Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?

Happy New Year and welcome to our first Arkadian analysis of 2012. Over the next five weeks we will be working towards the conclusion of the title of the series by exploring the answer to a simple question: –

Happy New Year and welcome to our first Arkadian analysis of 2012. Over the next five weeks we will be working towards the conclusion of the title of the series by exploring the answer to a simple question: –

“What difference between natural / social systems and the current economic system causes the former to tend towards diversity and stability, and the latter, uniformity and instability?”

In a world where the latter now poses a mortal threat to the former, we considered this to be a question of some significance. Could we learn from the way natural / social systems self-regulate in a way that benefits all, to design an ecologically-and-socially-just economic system?

Our analysis will be set out in five short articles, launching Friday mornings throughout January and early February: –

(1) Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability? Friday 6th January 2012.

(2) Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability? Friday 13th January 2012.

(3) Why do Diverse Systems = Stable Systems? Friday 20th January 2012.

(4) Why does the Current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability? Friday 27th January 2012.

(5) How do we create a Diverse and Stable Economic System? Friday 28th September 2012.

So without further ado, let’s move onto our first question of the series:

Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?

As a general rule the longer that ecosystems remain undisturbed by external factors, the richer they become. The oldest – the rainforests – are estimated to hold over half of all species, despite covering only 6% of the Earth’s surface. Why should 70m years of evolution against a backdrop of dynamic climate fluctuations give rise to increasing variety and not just a few dominant species?

MODEL 1 of our analysis below proposes an answer (N.B. If you have trouble reading the text, click on the diagram to open it in a new browser tab and then refer back to the explanation here).

Begin at the topmost variable and follow the arrows clockwise around the loop. (1) Put yourself in the position of a species that pursues total dominance over its local environment. (2) Despite considerable early successes, it’s not long before your manipulation and consumption begin to impact adversely on other species. (3) As local biodiversity diminishes, so too do the health, resilience and stability of the ecosystem as a whole, (4) resulting in ever-tighter constraints on your actions and, ultimately, the collapse of the environment upon which your own survival depends. (5) Your extinction kills off that suicidal gene that motivated your thirst for dominance, leaving an open stage for adaptive strategies that promote ecosystemic diversity and stability.

Begin at the topmost variable and follow the arrows clockwise around the loop. (1) Put yourself in the position of a species that pursues total dominance over its local environment. (2) Despite considerable early successes, it’s not long before your manipulation and consumption begin to impact adversely on other species. (3) As local biodiversity diminishes, so too do the health, resilience and stability of the ecosystem as a whole, (4) resulting in ever-tighter constraints on your actions and, ultimately, the collapse of the environment upon which your own survival depends. (5) Your extinction kills off that suicidal gene that motivated your thirst for dominance, leaving an open stage for adaptive strategies that promote ecosystemic diversity and stability.

Thus, coming full circle, (1) Your Environmental Dominance Strategy proved self-defeating because it led to Ecosystemic Weaknesses that constrained and, ultimately, negated, You! In Systems Dynamics a feedback loop like this where the impact of a variable is reduced by the effects it causes is called a ‘Balancing Circle’.

A further notable dynamic here is a pair of ‘Virtuous Circles’ (feedback loops where one delight leads to effects that enhance the first delight, and so on), which we’ve termed the ‘The Diversity Engine’.

A further notable dynamic here is a pair of ‘Virtuous Circles’ (feedback loops where one delight leads to effects that enhance the first delight, and so on), which we’ve termed the ‘The Diversity Engine’.

Here, (6a) the more the processes of natural selection incline towards interdependence, the more opportunities are opened up for new evolutionary adaptations. Thus, through increasingly fine-grained cooperation and specialisation between species, diversity itself drives diversity.

Moreover, as the environment grows ever more rich and complex, (6b) species dominance becomes increasingly futile and improbable, removing a further constraint on the trend towards diversity. And so both circles turn.

But (we hear you say) isn’t there a species that has had a radical effect on its local environment but has (thus far) escaped extinction? We hope you’ll drop in next Friday for Part 2, when we shall be exploring the curious exception of Homo Sapiens.

What the One Demand of the ‘Occupy’ Movement should be and why.

Today was Occupy Wall Street’s first Global Day of Action. We’re on our way home from our local urban occupation, feeling inspired, hopeful and slightly unsettled. Inspired and hopeful because people of all ages and backgrounds from around the world joined in protest against a corrupt economic system; unsettled due to a heated difference of opinion about what to do and who to battle (thankfully, and topically, resolved democratically and peaceably).

History is strewn with social movements that imploded through infighting, or where, for lack of a clear aim, the chaotic forces of moral indignation were steered by groups, with a plan and organisation, towards their own agenda (and, usually, more of the same). For either to happen to this beautiful movement would be a tragedy of inestimable proportions.

So is there a single aim that could unite the 99%?

The answer to this, we believe, lies in a further question: how is it that in a democratic system the 99% can be so flagrantly disregarded? This points to a problem with the machinery of Democracy itself. Perhaps, if we could locate the faulty part and fix or replace it, these diverse opinions would be enriching collective solutions rather than jeopardising their own vehicle for liberation?

There follows a 2-part systems dynamics analysis to this end.

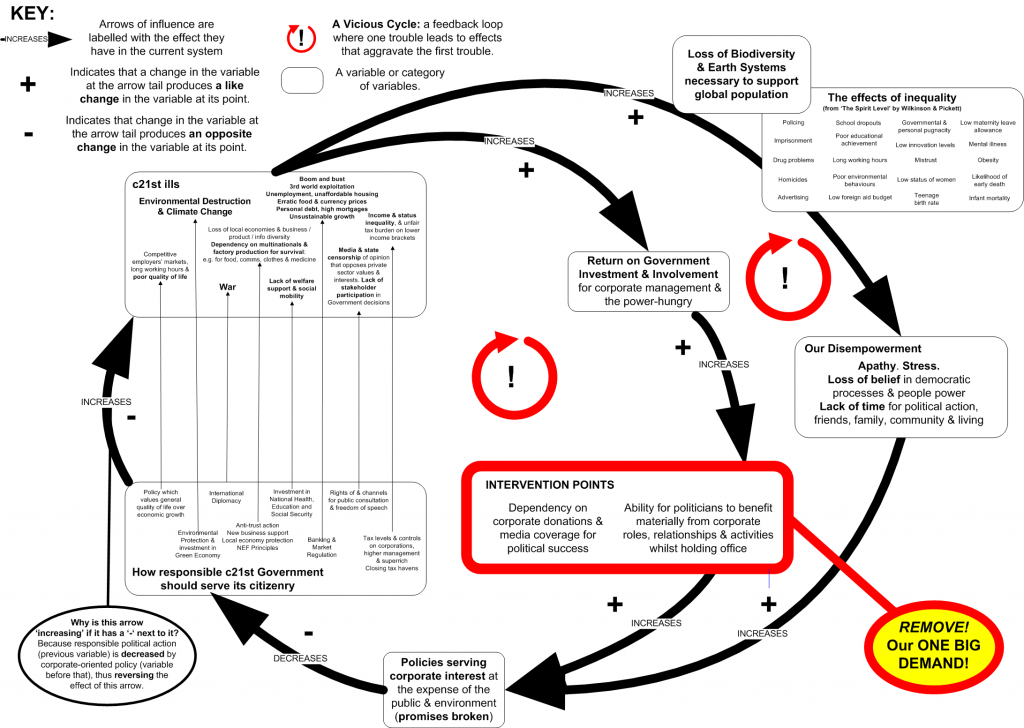

PART 1 proposes two Vicious Circles at work in the current system. These are series of events where one trouble leads to troubles that further aggravate that first trouble, and so on

(N.B. It’s easiest to click on the diagram to open it in a new browser and then refer back to the explanation here. Depending on your screen size, you may also need to zoom in-and-out in order to read the smaller text by clicking on the relevant area).

The best place to start is at the bottom where government policies that serve corporate interests are pursued at the expense of those that serve the 99% and the natural environment.

Whilst this enriches the 1% and motivates them to even greater future investments in manipulating Government policy (the 1st Vicious Circle – inner), it also exacerbates a range of hugely-profitable (in the short-term) c21st century ills: war, recession, inequality, loss of public services and assets, our increasing dependency on corporations for life’s essentials and, most critically, a severe threat to Earth’s life systems.

These factors, together with diminishing quality-of-life and broken political promises intensify our apathy and denial, and reduce time or inclination for political action, thus eroding a key constraining factor on the corporate policy abuses with which we began (the 1st Vicious Circle – outer). And so the Circles turn.

The analysis suggested two potential intervention points (highlighted in red) where action could positively transform the Vicious Circles. These are: –

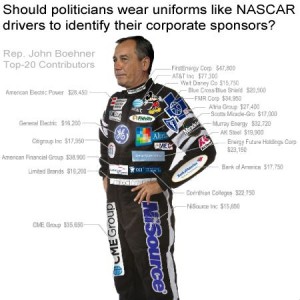

(1) Dependency on corporate relationships for political success. In short, a business wouldn’t bestow cash or media coverage on a political campaign that didn’t promise a significant return on investment. A third of the world’s 100 largest economic entities are now transnational corporations. Without bowing to these giants, no party has a hope of achieving or maintaining office, irrespective of good intentions and promises. Why pursue a policy or preserve a public service, asset, safeguard or freedom when losing it stands to make somebody a tidy profit?

(2) Ability for politicians to benefit materially from political office as a result of corporate relationships. Whilst we do not share many of Plato’s views (on Democracy, for example), we do agree that the worst form of government is one where the actions that satisfy the desires of the ruler become law. A tyranny. It was with good reason that The Republic went to great pains to isolate its philosopher kings from the temptation of riches and military stardom, the great corruptors of wise governance.

Under the Republic, for example, a former Prime Minister who made $40bn out of a dubious war he instigated whilst in office or a secret council assembled to draft laws to serve its own self-interest would have faced certain execution.

To put it simply, if we wish our countries to be run by people motivated by a desire to serve its citizenry and not by material self-interest then, within the political sphere, constraints on the latter must be codified in law and regulated independently. After all, corporate management takes conflict-of-interest very seriously. They know, as Plato did, that a person cannot responsibly wear two hats when money is involved.

To put it simply, if we wish our countries to be run by people motivated by a desire to serve its citizenry and not by material self-interest then, within the political sphere, constraints on the latter must be codified in law and regulated independently. After all, corporate management takes conflict-of-interest very seriously. They know, as Plato did, that a person cannot responsibly wear two hats when money is involved.

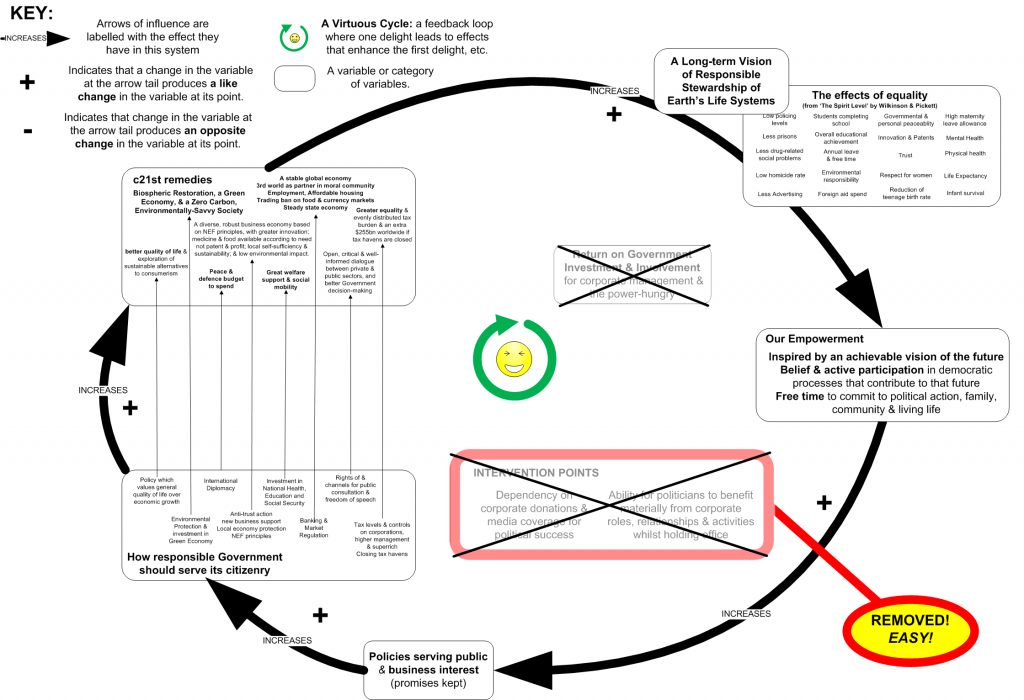

For PART 2 of the analysis the ‘Occupy’ Movement collectively waves its magic wand and divorces the public and private sectors, turning our Vicious Circles into its cheerful alter ego, a Virtuous Circle, where a delight leads to delights that further promote the first delight, and so on

(N.B. Again, it’s easiest to click on the diagram to open it in a new browser and then refer back to the explanation here. Depending on your screen size, you may also need to zoom in-and-out in order to read the smaller text by clicking on the relevant area)

Here, diverse opinion (with better access to information about actual environmental and economic constraints) is braided via participatory democratic processes and well-behaved politicians into policies that best serve both public and private interest.

This leads to a host of positive socioenvironmental effects that increase faith in people-power, government and the future. It also confers the time to get involved, thus contributing to even greater participation and ever richer solutions. And so the Virtuous Circle turns: driven by a commitment to a better world in the long-term.

Call us idealistic, but we believe this vision of an equitable sustainable society where stakeholders are actively engaged in Government is wholly imaginable, achievable and necessary. Moreover, It will not require earth-shattering change and would improve general quality-of-life.

However, we acknowledge that, as evidence of the Arkadian worldview – steady state economics, new economics principles, Just Transition , equality, environmental restoration, nurturing new values etc. – seeps in here, it would be best to declare the pertinent aspects. We ask that anybody who posts comments extends us the same courtesy as it makes discussion of opinions easier and so much more fruitful.

“Arkadian Systems Worldview: That the current economic system has been proven environmentally unsustainable and thus we must explore and enact alternatives or risk socioenvironmental collapse and extinction. That social and environmental justice are so intimately intertwined that treatment of one leads inevitably to reinforcing effects on the other. That decision-making is always wiser when all stakeholders with an interest in the relevant situation are meaningfully involved. ”

We should also stress that it is only the last of these – the principle underpinning a true Participatory Democracy – that should be considered relevant here. If Democracy is reformed and re-fired, we’re confident the rest will happen all by itself, the right way, and our opinion will be one of millions that make a contribution. So, to conclude,

The One Demand of the ‘Occupy’ Movement should be:

“GET BUSINESS OUT OF POLITICS AND LET THE PEOPLE IN”:

Insert a robust legal and regulatory framework between the private and public sectors, which enables Government to draft policy and law without conflict-of-interest and according to the principles of Participatory Democracy

Specifically, this framework should render it impossible for politicians to benefit materially from political office as a result of corporate relationships and should define equitable and corporate-independent alternatives to campaign funding .

For us, this is eminently preferable to smashing the bankers, police, politicians, Capitalism, Consumerism: THE SYSTEM. Trying to fight The System or one of its organs, inevitably results in giving oneself a bloody nose and the awful realisation that, yes, it also includes ME!

Recent Posts

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 3: Placing Mother Nature First

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 4: Ego-as-Process

- Charlie Hebdo and the Immorality Loop

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt3 (S America: #2-1)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt2 (S America: #7-3)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt1 (Africa, Asia, Europe & N America)

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 3: Freedom from the Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 2: The missing Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 2: The Principal Themes (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- What I Learned from Destroying the Universe

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

- The Root of all Evil: how the UK Banking System is ruining everything and how easily we can fix it.

- What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 4 of 5: Why does the current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 3 of 5: Why does A Diverse System = A Stable System?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 1 of 5: Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?