Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

Welcome to the final part in our series about social change strategy.

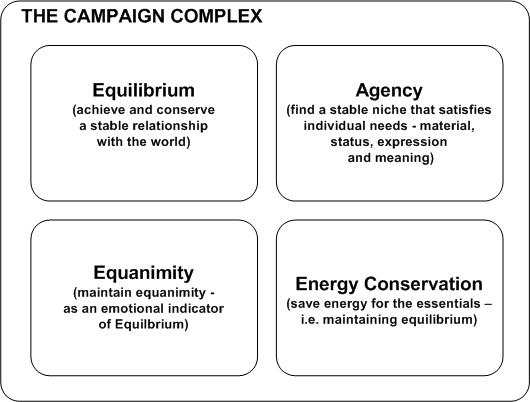

In part 1, we proposed a “Campaign Complex” comprised of four “biological” Principles – Equilibrium, Agency, Equanimity and Energy Conservation – which might account for some common challenges experienced by change agents. We outlined some strategies for successful campaigning suggested by these Principles.

In part 2, we proposed and discussed a “missing” fifth “Community Principle” implied by the other four, and suggested that some technologies – particularly transport and communications – may have facilitated its disintegration, by enabling “Agency” to bypass the constraints of geographical community.

In part 3, we discussed the benefits and costs associated with freedom from the “Community Principle”. We postulated that, ultimately, cultural and personal costs outweigh the benefits, and that resulting vicious circles may underpin and reinforce common campaigning bugbears.

In this final part, we will outline a Case Study which illustrates some of the positive characteristics of the Campaign Complex, particularly the Community Principle. We also propose the control parameters responsible for the re-emergence of the Principle in this context, and the implications it could have for change-oriented organisations.

Reactivating the Community Principle

In recent years, communities around the world have begun to exhibit a profound collective response to environmental crisis and encroachment by harmful industrial development.

This has frequently been sparked by onshore unconventional gas development (“fracking”, coalbed methane or coal seam gas, and underground coal gasification). Notable exemplars include the Community Bill of Rights Movement in the USA, and the “Lock the Gate” Alliance in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales, Australia.

One such case, of which Arkadian has first hand experience, is the Falkirk Against Unconventional Gas campaign. This began in September 2012, when residents of a Scottish community received notification of a proposal by Dart Energy to extract coal bed methane near their homes – the UK’s first application to commercialise the Dash-for-Gas.

Fragmented information-sharing initiatives by community councils and local residents soon coalesced into a series of general public meetings. Here, individual concerns about impacts on health and property values evolved into a general concerns about a common threat to community Equilibrium and Equanimity.

Meetings were supported by structured group decision-making and independent third-party facilitation. These processes complemented the Agency Principle by enabling a diverse group of residents to pool individual expertise and share equal ownership of outcomes.

The collective response emerged in the form of two groundbreaking documents.

The first was a pro-forma objection letter – the Community Mandate – which began with the community’s visions of 20yrs in the future – one born from local council policy and residents’ aspirations, and the second, what the area might look like if the industry rolled out. It also set out residents’ evidence for suspected risk and their own minimum requirements for its assessment and regulation.

3 months later, over 2500 had been signed and submitted, including representation by over 80% of some affected villages.

A group of residents, each with modest door-knocking goals (satisfying the Energy Conservation Principle) in a short time achieved the biggest response to a planning application in the history of the local authority.

The second document – the UK’s first Community Charter – wholly redefined the narrative from “fighting against” to “fighting for”. Drawing from the Mandate’s positive vision, the Charter set out those shared assets, values and aspirations – termed “Cultural Heritage” – which were agreed by consensus to be fundamental to local health and well-being.

Assets, agreed unanimously, included the goal of a clean and safe environment, the healthy development of children, the sanctuary of the home, the diversity and stability of the local ecosystem, the resilience and continuity of the community. and trust in elected representatives.

The Charter also set out the community’s basic right and responsibility to safeguard and improve their “Cultural Heritage”, in order that they could pass it onto future generations in a better state than they inherited it.

This provided a remarkably detailed and concrete definition of that notoriously slippery term: “sustainable development”. It also illustrates that it’s only really meaningful if delineated and maintained by general consent at a local level.

This broadening of “Cultural Heritage” to encompass the fabric of interrelationships that creates community, including both tangible and intangible assets, also finds support in the Council of Europe Framework Convention.

The Charter has since been adopted by 3 local Community Councils, half of all Local Authority Councilors and an ever-growing number of local farmers and residents. It was also recognised by Scottish Government as requiring a special session in the recent public inquiry to decide the application, the UK’s first in relation to the Dash-for-Gas. Here, and in later Hearing sessions (see below), local residents, farmers and councilors gave evidences about the impact of the development on their aspirations and experience.

Regardless of the outcomes of this public inquiry, nothing seems more likely to succeed, ultimately, than a community thinking and acting together to protect the shared fundaments of its Equilibrium and Equanimity.

And the Control Parameters?

1) A COMMON THREAT (AND PURPOSE) PERCEIVED;

2) A vision of what true Equilibrium and Equanimity look like (set out in the Community Mandate and Charter);

3) A few souls brave enough to cold-call an unknown neighbour;

4) Simple processes which supported collective assessment and decision-making (Agency Principle); and

5) Modest collective goals and successes at the outset (Community and Energy Conservation Principles).

That’s all!

It didn’t take much for people to feel re-empowered by the wisdom and the scale of what could be achieved together, and why this was important. Negotiating a diversity of perspectives has involved conflict and compromise (neither much appreciated by “Agency”), but the compensations have been more than worth the pain – collective vision and support, social learning, and novel opportunities for individual expression, powerful friendships, and fun.

Moreover, though Part 2 suggested some technologies facilitated the disintegration of Community, the same technologies here have played an invaluable role in maintaining strategic communications among residents, and with other community groups and experts across the globe. The technology itself is neutral and while it may offer “Agency” easy routes to self-satisfaction, in the service of collective purpose it has been a powerful mechanism to support face-to-face activities.

To conclude, in this light perhaps unconventional gas could represent a genuine opportunity for the UK, and not the one espoused by the industry and Government? The Dash-for-Gas represents a clear and immediate threat to thousands of communities. Unquestionably, costs at a local level outweigh the benefits. Two thirds of the UK are earmarked for exploitation.

Thus, key control parameters necessary for re-activating the Community Principle seem present and on an extensive scale. If the response by Falkirk, Canonbie, Balcombe, Fenhurst, Barton Moss, and many many others communities across the UK and the world, are harbingers of what’s to come, then we should be reassured and, indeed, get stuck in.

In the absence of a viable alternative to our current system, the power for transition lies not with the UN, or the EU or National Government, or in a strong brand or campaign, but emergent right on our doorstep. There is no political will without public will, and the Campaign Complex suggests the latter hinges on our participation in, and ownership of, the what, how and why of change.

Arkadian is coming to the view that such processes can only really be concrete, practical and meaningful in a local context, that they require people to get together in the same room, and that due to cultural and technological factors they’re unlikely to happen without certain control parameters in place, most notably a perceived common threat or purpose.

Nevertheless, there’s also no question that acting effectively, in concert, is a biological capacity conferred by evolution, and lies latent just below the surface despite Agency’s best efforts to deny and suppress it. Indeed, the balance conferred by the Community Principle may be the only thing now that can prevent Agency chasing money off the cliff with all in tow. The rewards of reactivation, on the other hand, seem manifold.

Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

This is a 4-part series which proposes a framework – the Campaign Complex – which may explain some common campaigning barriers and successes, and could inform practical strategy for community groups, campaigners and NGOs.

In Part 1, we outline the framework and its 4 component Principles, each of which may have a general adaptive purpose for all animals.

The idea of the Campaign Complex emerged from the analysis of a focus group of seasoned change agents, the loose aim of which was to explore how organisations with similar values, but different foci, might work in a more mutually-supportive way.

The discussion circle was structured around personal responses to the following three questions (written on post-its and stuck on the wall for reference during the conversation):

- 1) What motivates a change agent?

- 2) What are the barriers to a successful campaign?

- 3) What has worked at overcoming these barriers?

Despite the wide diversity of campaigning knowledge and experience in the mix – political party, banking reform, community gardening, social change, national Climate Change, Occupy, community opposition to unconventional gas – there was a surprisingly strong agreement on what had and hadn’t worked.

However, in the analysis, oft-cited barriers to success – ignorance, gullibility, apathy, carelessness and denial – seemed to offer an incomplete and superficial account of the themes.

The framework that emerged was much influenced by Arkadian’s concurrent involvement in local opposition to unconventional gas extraction, which offered first-hand experiences of positive and negative campaign dynamics, and also the author’s PhD Research, which is exploring child development from a biological systems perspective.

There follows an overview of the 4 Principles that make up the Campaign Complex, their proposed evolutionary adaptive purpose, how their effects manifest in our lives and their possible consequences for campaigns.

To close, we shall outline some of the Complex’s strategic implications for positive change.

THE CAMPAIGN COMPLEX

Purpose. The primary purpose of the animal nervous system is to construct and maintain a stable and predictable relationship with the immediate environment.

Purpose. The primary purpose of the animal nervous system is to construct and maintain a stable and predictable relationship with the immediate environment.

Effects. Once we’ve established a workable pattern of interrelationship with our everyday world – routines / capacities / opinions / property / social relations etc. – we will tend towards experiences which build on it, and avoid those which might threaten its integrity or interrupt its flow.

Consequences. Even when we intellectually or morally appreciate the goals of a campaign, meaningful engagement may be challenging if it entails any implication of change to our ways of life and thinking, or any risk of losing face, identity, property or employment. A perceived, possibly unconscious, threat to stability could be why change agents frequently encounter dismissive, disapproving or defensive responses from their immediate and wider society.

2) The Agency Principle:

Purpose. An individual animal’s primary directive is to negotiate and maintain the resources, territory and freedom necessary for successful survival, reproduction and self-fulfillment.

Purpose. An individual animal’s primary directive is to negotiate and maintain the resources, territory and freedom necessary for successful survival, reproduction and self-fulfillment.

Effects. We tend towards experiences which confer control over decisions important to our sense of material and social stability, which provide support and appreciation for our individual needs and expression, and avoid those where such agency is absent or at risk.

Consequences. We’re unlikely to commit to a campaign if we’ve no involvement in determining goals and activities, are insecure about the knowledge and skills it may require, or believe our contribution is insignificant or unappreciated. If we do, we may unconsciously undermine leadership and approaches, or overplay our role. On the other hand, when we lead, criticism of our good intentions may leave us feeling frustrated, confused and isolated.

3) The Equanimity Principle:

Purpose. Stress is the animal response to a threat to equilibrium or agency. It motivates flight or fight action with the goal of achieving the equanimity indicative of a stable experience of world and self.

Purpose. Stress is the animal response to a threat to equilibrium or agency. It motivates flight or fight action with the goal of achieving the equanimity indicative of a stable experience of world and self.

Effects. We will tend to avoid stressful information and experiences, unless they relate to an immediate and unavoidable danger, and seek those which confer individual reassurance and pleasure.

Consequences. By evading distressing truths, we often grow ignorant of the need for change the emotion is supposed to motivate. Without our sponsorship, vital sources of information and action fade or are curbed. By comfort-seeking, we often fuel toxic cycles of consumption – the c21st’s default route to well-being.

4) The Energy Conservation Principle:

Purpose. Animal behaviour largely presumes an erratic energy supply. Available resources are usually stockpiled and used frugally and efficiently to pursue equilibrium, agency and equanimity.

Purpose. Animal behaviour largely presumes an erratic energy supply. Available resources are usually stockpiled and used frugally and efficiently to pursue equilibrium, agency and equanimity.

Effects. We tend to avoid non-essential goals and tasks that entail, or might entail, unnecessary cognitive or physical energy or which someone else will tackle if we don’t, and favour those yielding maximum immediate reward for minimum effort.

Consequences. We are unlikely to engage with a campaign which implies long-term commitment, doubtful victory, a taxing work / info load, or which appears to be ticking along fine without us. On any given task, we will seek efficiencies and, given a range of ways of participating, we are likely to elect for the easiest.

STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS OF THE CAMPAIGN COMPLEX:

1) EQUILIBRIUM: Campaigns will have greater likelihood of success if they are perceived to be safeguarding what we collectively value and what is integral to the stability of our everyday lives. We are more likely to engage if we think we stand to lose or change more through our inaction, than our action. We are also likely to need significant practical and moral support for activities which are unfamiliar to us, no matter how basic they seem to others.

1) EQUILIBRIUM: Campaigns will have greater likelihood of success if they are perceived to be safeguarding what we collectively value and what is integral to the stability of our everyday lives. We are more likely to engage if we think we stand to lose or change more through our inaction, than our action. We are also likely to need significant practical and moral support for activities which are unfamiliar to us, no matter how basic they seem to others.

2) AGENCY: Campaigns with common purpose, which co-develop goals, roles and actions through facilitated, collective decision-making processes are more likely to work because they give us an opportunity to express agency and feel ownership of outcomes.

2) AGENCY: Campaigns with common purpose, which co-develop goals, roles and actions through facilitated, collective decision-making processes are more likely to work because they give us an opportunity to express agency and feel ownership of outcomes.

3) EQUANIMITY: Campaigns are most likely to motivate us if they address an immediate, common threat to equilibrium or agency, thus provoking a “fight” response. Moreover, visible evidence of support is, in turn, more likely to inspire action because “fighting” together is more likely to succeed (though it can also offer us a cover for inaction – see below).

3) EQUANIMITY: Campaigns are most likely to motivate us if they address an immediate, common threat to equilibrium or agency, thus provoking a “fight” response. Moreover, visible evidence of support is, in turn, more likely to inspire action because “fighting” together is more likely to succeed (though it can also offer us a cover for inaction – see below).

Collective action will provide further reinforcement if it also offers us opportunities for fun, enjoyment and socializing. Such activities could also mitigate the risk of campaign disintegration as the result of stress causing us to become preoccupied with our own self-preservation, and lose sight of the needs and goals of the group (the dynamics of which will be explored in Pt 2).

4) ENERGY CONSERVATION. Simple first-step experiences, which imply no commitment but deliver rewards that resonate strongly with the other principles, are most likely to facilitate our deepening involvement. Regular “heartbeat” meetings and events can promote habits which override our excuses and inertia.

4) ENERGY CONSERVATION. Simple first-step experiences, which imply no commitment but deliver rewards that resonate strongly with the other principles, are most likely to facilitate our deepening involvement. Regular “heartbeat” meetings and events can promote habits which override our excuses and inertia.

Lastly, if our engagement tails off, we need carefully-worded unemotional feedback about the potential consequences of our inaction. If we don’t know our non-participation threatens what we value, then this principle predicts we’re unlikely to do anything about it.

So there’s the Campaign Complex in a nutshell. We hope you’ll join us next Friday for Part 2, when we shall be proposing a vital “Missing Principle” inferred from the dynamics and implications discussed here.

What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

This article is about a ‘whole systems thinking’ session Arkadian ran with 15 Occupy followers of all ages and backgrounds. All participants were required to answer 3 questions: –

(1) What is Occupy’s purpose; (2) How should this purpose be achieved and; (3) Why was it important?

Personal thoughts were written on post-its, stuck on a wall, and organised by the group according to content similarity and difference. The discussion fueled by these activities gave rise to 6 collective insights (the 7th is an insight Arkadian derived from the others): –

(1) Occupy is a grass-roots, direct-democratic movement

(1) Occupy is a grass-roots, direct-democratic movement

(2) Occupy is ‘about’ co-creating and enacting a Viable Alternative to the current system

(3) The Viable Alternative is a collective vision

(4) Achieving the Viable Alternative requires building critical mass

(5) Building critical mass depends on making the Viable Alternative simple, relevant and clear to the wider population

(6) Aims could be best achieved through grass-roots ‘campaigns’ connecting the Viable Alternative to local community issues

(7) These insights had implications for Occupy’s organisational design

There follows a brief explanation of each: –

1. Occupy is a grass-roots, direct-democratic movement: All followers saw Occupy as ‘of the people / for the people’, independent of, and transcending all, other organisations. There was genuine concern that ‘partnerships’, or Occupy chapters becoming formal or political entities, would compromise the essential qualities of this idea. Nevertheless, it was also acknowledged that high profile support could, and had, delivered some powerful PR.

The solution proposed was that ‘partnerships’ should always be one-way and arms-length only, i.e. limited to inviting, or allowing, third parties to sign up to Occupy’s (viz: ‘the people’s’) aims and principles. But what aims and principles?

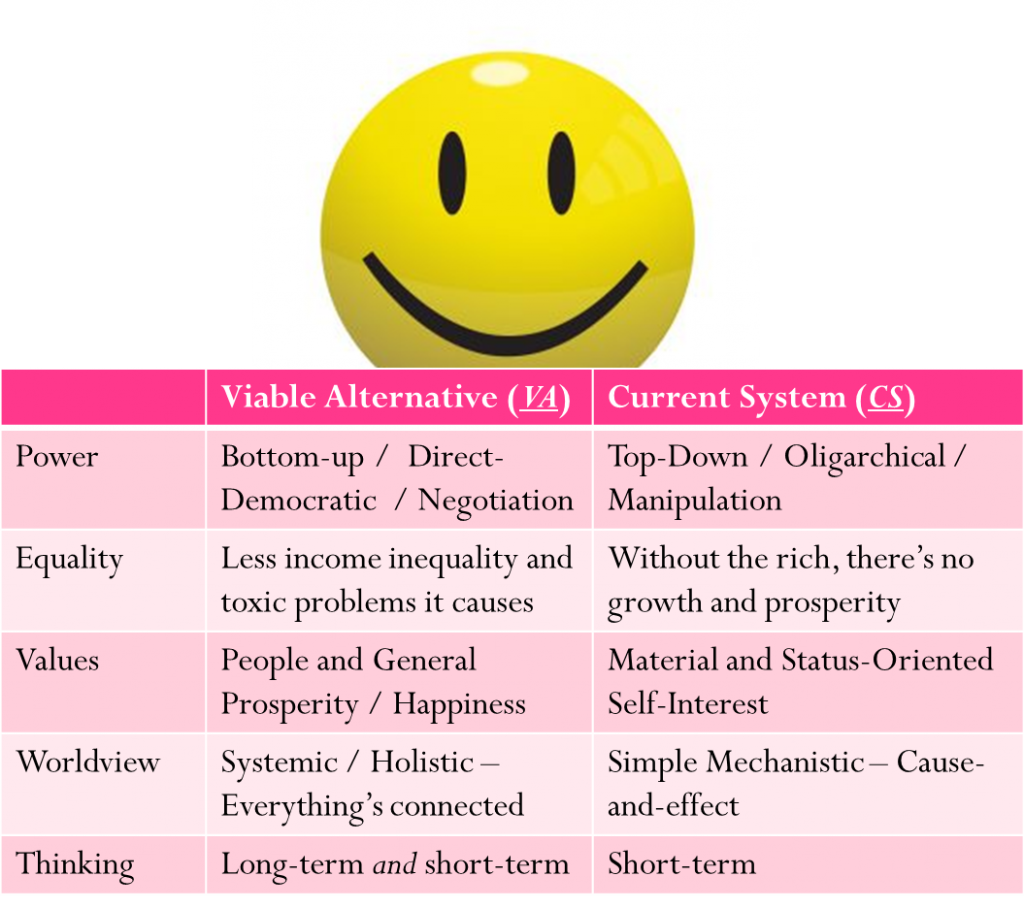

2. Occupy is ‘about’ co-creating and enacting a Viable Alternative to the current system: The most powerful theme that emerged in the discussion. To get a handle on some of the structural principles of this Viable Alternative, ask yourself the following questions…

Power: Would the world be better if people had greater involvement in decisions that affect their lives and future?

Equality: Would the world be better if the gap between rich and poor were reduced? (N.B. Not to a ‘ Communist’ extreme, merely a lessening of the vast multipliers separating high / low incomes and developing / developed nations, and their toxic impact on society and environment).

Equality: Would the world be better if the gap between rich and poor were reduced? (N.B. Not to a ‘ Communist’ extreme, merely a lessening of the vast multipliers separating high / low incomes and developing / developed nations, and their toxic impact on society and environment).

Values: Would the world be better if quality of life and well being were valued over material and status-driven self-interest?

Worldview: Are the big social, environmental and economic challenges connected in any way? Might addressing one have beneficial effects on others?

Thinking: Should the well being of future generations and the long-term viability of life on our planet be important to current decision-making?

If you answered ‘Yes’ to any, or all, of these questions then you’re ‘Occupy’. Below is a rough summary table comparing the principles of the Viable Alternative to those of the current system.

So what actions does all this imply? Firstly, if they are widely shared, then these structural principles could provide the ideal framework for coherent organisation, action and communications, and solidarity, across diverse contexts.

Secondly, the Viable Alternative is a positive idea: it’s about a happier, better future. Whilst its necessary to highlight why change is necessary, negative news and arguments about the nitty-gritty can drive people away. Emphasising these higher-level, common and cheerful principles, on the other hand, could score greater successes with the wider population.

3. The Viable Alternative is a collective vision: The whole group shared a belief in the urgent necessity for the Viable Alternative, which in turn, seemed dependent upon an understanding of the scale and interconnectedness of the issues.

However, each individual held their own beliefs about what the important problems were, how they were connected, and the appropriate remedies and actions: a product of their life experiences, personal interests and, for many, exposure to new information since engaging with the movement.

Nevertheless, the post-its-on-the-wall represented a truly epic mess, one that evidently required highly situation-specific solutions, each of which defied the analytic or predictive capabilities of any ‘expert’. Recognition of this within the group seemed to drive processes where individual experiences were tools for building, negotiating and informing a dynamic picture of NOW, in order to decide the best next step(s) only, not the grand master plan.

Rather than disagreements about which view was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, all views seemed appreciated as valuable and partially right. In a sense, the group behaved like a ‘super-brain’, leveraging many lifetimes’ worth of perspectives, knowledge and experience to reach wise ‘objective’ assessments and decisions about an impossibly complex ‘subjective’ situation.

Rather than disagreements about which view was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, all views seemed appreciated as valuable and partially right. In a sense, the group behaved like a ‘super-brain’, leveraging many lifetimes’ worth of perspectives, knowledge and experience to reach wise ‘objective’ assessments and decisions about an impossibly complex ‘subjective’ situation.

So what are the implications of all this? Firstly, if collaborative decision-making can be so individually empowering and collectively clever, then all Occupy followers should be furnished with simple group moderation skills and ‘whole systems’ tools. Processes that focus discussions on external representations (pictures / post-its / models etc.) should become a sine qua non of the movement.

Secondly, the movement should stress that, whilst expressing a personal view is the inalienable right of any follower, unless its braided into a collective decision, it ain’t Occupy!

Lastly, if action is motivated by seeing the connections between disparate social, economic and environmental issues, then Occupy should underscore ‘stories’ that highlight the ‘connections’, and fast track new members into contributing to collective decision-making – judging by the discussion, it’s difficult not to ‘join-the-dots’ when exposed to the Occupy ecology.

Lastly, if action is motivated by seeing the connections between disparate social, economic and environmental issues, then Occupy should underscore ‘stories’ that highlight the ‘connections’, and fast track new members into contributing to collective decision-making – judging by the discussion, it’s difficult not to ‘join-the-dots’ when exposed to the Occupy ecology.

(4) Achieving the Viable Alternative requires building critical mass: Reflection upon this fact led rapidly to the recognition that human and financial resources were critical priorities, and that there were probably no shortcuts to them.

(5) Building critical mass depends on making the Viable Alternative simple, relevant and clear to the wider population: The second dominant theme of the session. To successfully engage the wider population, it was deemed Occupy needed communications that were simple, relevant to the differing needs of specific target audiences, and employed clear popularly-understood terminology pitched at the appropriate level of understanding, e.g. stock phrases like ‘socioeconomic justice’ and ‘ecological limits’ were not understood by many in the group. It was also considered important that these messages were backed-up by incontestable evidence and sources, and communicated solidarity.

Everyone also acknowledged this would entail outwitting the ‘guardians’ of the current system ‘at their own game’, exploring channels that they don’t, or can’t easily, command, and responding quickly and devastatingly to opposition. The discussion highlighted that intelligent, reflective information management – researching, screening, organising, tailoring – was central to Occupy’s role and ultimate success.

So, to recap. Occupy needs to…

(i) Organise without being an organisation.

(ii) Communicate a Viable Alternative when no-one can know what it is, and where it is only made manifest via specific situations and perspectives.

(iii) Create an outward appearance of solidarity when structured disagreement is an essential requirement.

(iv) Use channels not covered by the ubiquitous guardians of the current system, whilst building volunteers, funds and critical mass.

What solution to these challenges did the collective propose?

(6) Grass-roots ‘campaigns’ connecting the Viable Alternative to local community issues: Explore and discuss ‘issues’ door-to-door. Those that resonate, have local relevance, and are aligned with the Viable Alternative could then become the focus of grass-roots campaigns, building to direct ‘visible’ action, and all informed by Occupy’s structural principles, particularly, inclusive community decision-making. Not talking and blaming, but showing the world how things could be: through small-scale collaborative achievement and learning.

(6) Grass-roots ‘campaigns’ connecting the Viable Alternative to local community issues: Explore and discuss ‘issues’ door-to-door. Those that resonate, have local relevance, and are aligned with the Viable Alternative could then become the focus of grass-roots campaigns, building to direct ‘visible’ action, and all informed by Occupy’s structural principles, particularly, inclusive community decision-making. Not talking and blaming, but showing the world how things could be: through small-scale collaborative achievement and learning.

(7) These previous 6 insights had implications for Occupy’s organisational design: The final insight, Arkadian’s own, was that attaining all of the previous objectives implied a radically new organisational design, lest rapid growth give rise to hierarchy – the spoiling of many a revolution and NGO, and, in Occupy’s case: a fundamental hypocrisy.

A model where multiple ‘cross-pollinating’ cells are structured around local campaigns / action and mutually agreed principles of the Viable Alternative, perhaps? For a future session…

So, to conclude, at Occupy’s heart is a Viable Alternative that really is the current system turned on its head. A total paradigm shift, but a necessary one, if we are to share a remotely tolerable future.

Moreover, maybe change is easier than it seems. After all , the principles of the Viable Alternative are neither unfamiliar nor new, are they? Arguably, they, and not those of the current system, have determined how we cooperate with our nearest and dearest since time immemorial. We just need to realise the whole world could and should work this way.

What the One Demand of the ‘Occupy’ Movement should be and why.

Today was Occupy Wall Street’s first Global Day of Action. We’re on our way home from our local urban occupation, feeling inspired, hopeful and slightly unsettled. Inspired and hopeful because people of all ages and backgrounds from around the world joined in protest against a corrupt economic system; unsettled due to a heated difference of opinion about what to do and who to battle (thankfully, and topically, resolved democratically and peaceably).

History is strewn with social movements that imploded through infighting, or where, for lack of a clear aim, the chaotic forces of moral indignation were steered by groups, with a plan and organisation, towards their own agenda (and, usually, more of the same). For either to happen to this beautiful movement would be a tragedy of inestimable proportions.

So is there a single aim that could unite the 99%?

The answer to this, we believe, lies in a further question: how is it that in a democratic system the 99% can be so flagrantly disregarded? This points to a problem with the machinery of Democracy itself. Perhaps, if we could locate the faulty part and fix or replace it, these diverse opinions would be enriching collective solutions rather than jeopardising their own vehicle for liberation?

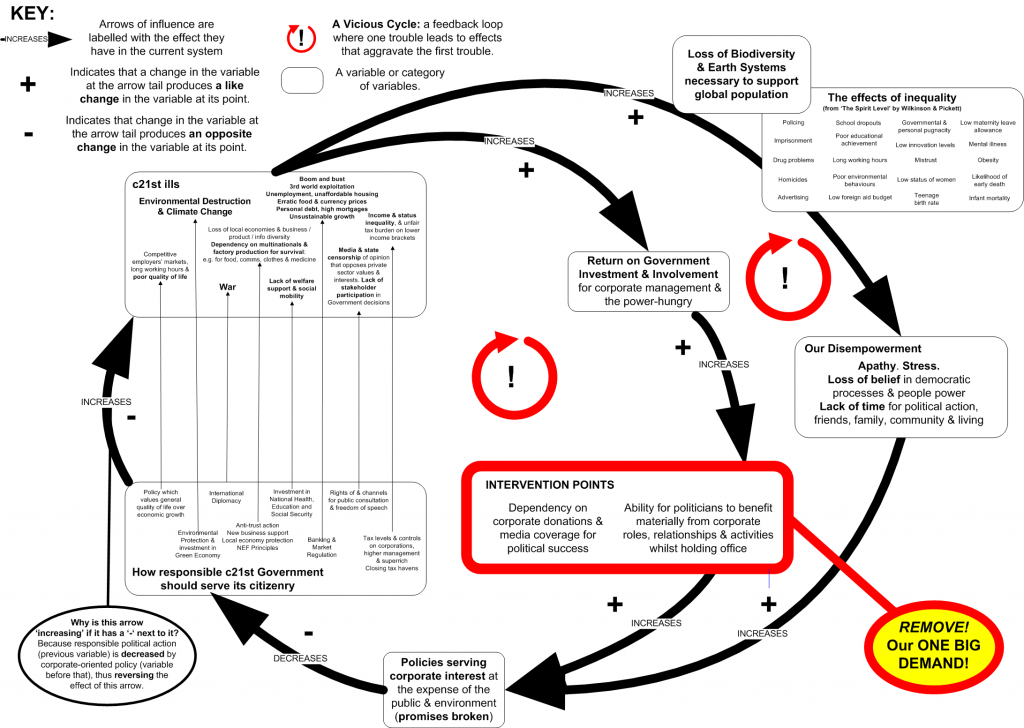

There follows a 2-part systems dynamics analysis to this end.

PART 1 proposes two Vicious Circles at work in the current system. These are series of events where one trouble leads to troubles that further aggravate that first trouble, and so on

(N.B. It’s easiest to click on the diagram to open it in a new browser and then refer back to the explanation here. Depending on your screen size, you may also need to zoom in-and-out in order to read the smaller text by clicking on the relevant area).

The best place to start is at the bottom where government policies that serve corporate interests are pursued at the expense of those that serve the 99% and the natural environment.

Whilst this enriches the 1% and motivates them to even greater future investments in manipulating Government policy (the 1st Vicious Circle – inner), it also exacerbates a range of hugely-profitable (in the short-term) c21st century ills: war, recession, inequality, loss of public services and assets, our increasing dependency on corporations for life’s essentials and, most critically, a severe threat to Earth’s life systems.

These factors, together with diminishing quality-of-life and broken political promises intensify our apathy and denial, and reduce time or inclination for political action, thus eroding a key constraining factor on the corporate policy abuses with which we began (the 1st Vicious Circle – outer). And so the Circles turn.

The analysis suggested two potential intervention points (highlighted in red) where action could positively transform the Vicious Circles. These are: –

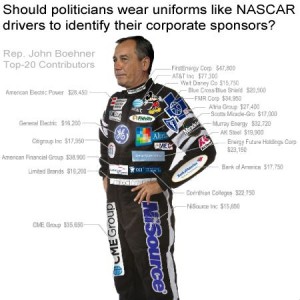

(1) Dependency on corporate relationships for political success. In short, a business wouldn’t bestow cash or media coverage on a political campaign that didn’t promise a significant return on investment. A third of the world’s 100 largest economic entities are now transnational corporations. Without bowing to these giants, no party has a hope of achieving or maintaining office, irrespective of good intentions and promises. Why pursue a policy or preserve a public service, asset, safeguard or freedom when losing it stands to make somebody a tidy profit?

(2) Ability for politicians to benefit materially from political office as a result of corporate relationships. Whilst we do not share many of Plato’s views (on Democracy, for example), we do agree that the worst form of government is one where the actions that satisfy the desires of the ruler become law. A tyranny. It was with good reason that The Republic went to great pains to isolate its philosopher kings from the temptation of riches and military stardom, the great corruptors of wise governance.

Under the Republic, for example, a former Prime Minister who made $40bn out of a dubious war he instigated whilst in office or a secret council assembled to draft laws to serve its own self-interest would have faced certain execution.

To put it simply, if we wish our countries to be run by people motivated by a desire to serve its citizenry and not by material self-interest then, within the political sphere, constraints on the latter must be codified in law and regulated independently. After all, corporate management takes conflict-of-interest very seriously. They know, as Plato did, that a person cannot responsibly wear two hats when money is involved.

To put it simply, if we wish our countries to be run by people motivated by a desire to serve its citizenry and not by material self-interest then, within the political sphere, constraints on the latter must be codified in law and regulated independently. After all, corporate management takes conflict-of-interest very seriously. They know, as Plato did, that a person cannot responsibly wear two hats when money is involved.

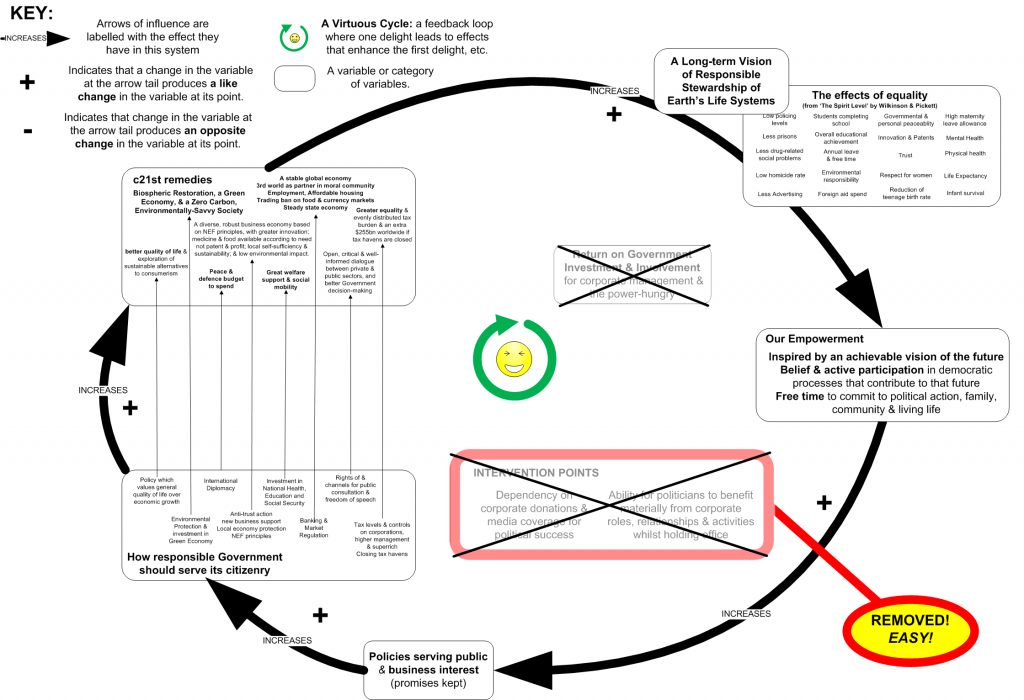

For PART 2 of the analysis the ‘Occupy’ Movement collectively waves its magic wand and divorces the public and private sectors, turning our Vicious Circles into its cheerful alter ego, a Virtuous Circle, where a delight leads to delights that further promote the first delight, and so on

(N.B. Again, it’s easiest to click on the diagram to open it in a new browser and then refer back to the explanation here. Depending on your screen size, you may also need to zoom in-and-out in order to read the smaller text by clicking on the relevant area)

Here, diverse opinion (with better access to information about actual environmental and economic constraints) is braided via participatory democratic processes and well-behaved politicians into policies that best serve both public and private interest.

This leads to a host of positive socioenvironmental effects that increase faith in people-power, government and the future. It also confers the time to get involved, thus contributing to even greater participation and ever richer solutions. And so the Virtuous Circle turns: driven by a commitment to a better world in the long-term.

Call us idealistic, but we believe this vision of an equitable sustainable society where stakeholders are actively engaged in Government is wholly imaginable, achievable and necessary. Moreover, It will not require earth-shattering change and would improve general quality-of-life.

However, we acknowledge that, as evidence of the Arkadian worldview – steady state economics, new economics principles, Just Transition , equality, environmental restoration, nurturing new values etc. – seeps in here, it would be best to declare the pertinent aspects. We ask that anybody who posts comments extends us the same courtesy as it makes discussion of opinions easier and so much more fruitful.

“Arkadian Systems Worldview: That the current economic system has been proven environmentally unsustainable and thus we must explore and enact alternatives or risk socioenvironmental collapse and extinction. That social and environmental justice are so intimately intertwined that treatment of one leads inevitably to reinforcing effects on the other. That decision-making is always wiser when all stakeholders with an interest in the relevant situation are meaningfully involved. ”

We should also stress that it is only the last of these – the principle underpinning a true Participatory Democracy – that should be considered relevant here. If Democracy is reformed and re-fired, we’re confident the rest will happen all by itself, the right way, and our opinion will be one of millions that make a contribution. So, to conclude,

The One Demand of the ‘Occupy’ Movement should be:

“GET BUSINESS OUT OF POLITICS AND LET THE PEOPLE IN”:

Insert a robust legal and regulatory framework between the private and public sectors, which enables Government to draft policy and law without conflict-of-interest and according to the principles of Participatory Democracy

Specifically, this framework should render it impossible for politicians to benefit materially from political office as a result of corporate relationships and should define equitable and corporate-independent alternatives to campaign funding .

For us, this is eminently preferable to smashing the bankers, police, politicians, Capitalism, Consumerism: THE SYSTEM. Trying to fight The System or one of its organs, inevitably results in giving oneself a bloody nose and the awful realisation that, yes, it also includes ME!

Recent Posts

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 3: Placing Mother Nature First

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 4: Ego-as-Process

- Charlie Hebdo and the Immorality Loop

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt3 (S America: #2-1)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt2 (S America: #7-3)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt1 (Africa, Asia, Europe & N America)

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 3: Freedom from the Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 2: The missing Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 2: The Principal Themes (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- What I Learned from Destroying the Universe

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

- The Root of all Evil: how the UK Banking System is ruining everything and how easily we can fix it.

- What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 4 of 5: Why does the current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 3 of 5: Why does A Diverse System = A Stable System?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 1 of 5: Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?